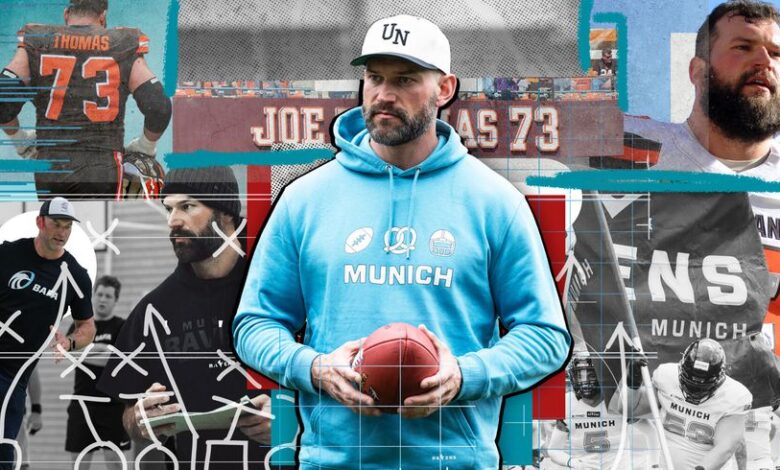

Joe Thomas Shares His Journey to Germany to Coach Pro (American) Football

WHEN JOE THOMAS retired from the NFL in 2018, his wife Annie made it clear where she expected him to dedicate his attention going forward. “It’s family time,” he recalls her saying. “You don’t have an excuse to go to work every day, 50 hours a week or more.” The former Cleveland Browns star had four kids; the time immediately following his retirement were going to be peak dad years. “My wife has done a really good job of making sure that I understand that . . . your kids are only going to be kids once.”

But after 11 seasons in the NFL, the Hall of Fame offensive tackle still wanted to stay close to the gridiron. And more than that, he wanted to coach—even though he knew that the commitment to game planning and craft stood at odds with his commitment to family time.

Six years later, after stints as an NFL Network broadcast analyst, podcast host, and volunteer youth coach, he’s found the perfect compromise. Joe Thomas, one-time immovable offensive lineman, is spending this spring and summer as the Ravens offensive line coach. But no, we don’t mean the NFL’s Baltimore Ravens. Thomas is coaching the Ravens in Munich. (As in Munich, Germany.)

Thomas lined up at his left tackle position for the Cleveland Browns.

The Munich Ravens are a franchise in the European League of Football (ELF), a fledgling pro American football league that includes 17 teams in nine countries across the continent —and it just may be the perfect place for Thomas, who announced he would head over to Munich midway through last year. That led to a collective “they have pro football in Germany?” from plenty of NFL fans.

But Thomas is enjoying his unique road to coaching. By trekking to Munich, he’s simultaneously gaining valuable coaching experience and serving as a global ambassador for the sport he loves while still prioritizing his family. I caught up with Thomas on a call from Munich (more accurately, as he drove home from a ski outing in Austria, just another perk of his unconventional gig) to hear his story.

THOMAS ADMITS HE didn’t know much about football outside the US before traveling to Munich with the NFL Network to cover the league’s first regular season game in Germany in 2022, part of the league’s ongoing International Series that has staged contests in London, Mexico City, and Germany since 2007. While taking in the city’s festivities surrounding the event, he guested on a live podcast recording that was attended by more than 5,000 fans who Thomas says were “going absolutely bonkers.”

Thomas also reconnected with one of the show’s hosts, Patrick Esume, a German-born football figure who worked with the Browns as part of the NFL’s Minority Coaching Fellowship in 2007, Thomas’s rookie year. Esume, now the ELF’s commissioner, told Thomas how American football was growing in Germany. “That’s when I started thinking there’s really a chance that I can come over here and we can live out a little bit of a dream of living abroad for a while, while coaching,” Thomas says.

Most US-based football fans know little of the sport’s expansion beyond North American soil beyond the NFL’s 17-year-old International Series. Those games include hordes of Europeans cheering from the stands wearing mismatched team jerseys, who are mostly excited to see their favorite sport in person, no matter which teams take the field. But there’s even more love for more than just NFL football than that, says Thomas. “It’s really cool seeing the passion for American football over here in Germany,” Thomas says. “You can tell that there is a passion for American football over here that’s really untapped.”

Munich Ravens players during ELF competition.

Enter the ELF, which started in 2021 (the Munich Ravens’ first season was 2023) and is just the latest European attempt to establish legitimate pro American football abroad. Before that came NFL Europe, a US-affiliated developmental league that folded in 2007, and a constellation of other semi-pro club confederations across the continent. Most of these leagues asked European players to pay membership “dues” while paying Americans to play key positions (think QB) and coach as “imports.” The ELF actually pays all players, although it still depends on American import talent.

Thomas talked to his family about heading to Munich last year, and they made the move in January, well ahead of the ELF season, which begins in late May and wraps in mid-September. Since then, he’s immersed himself in preseason training sessions with players while still working to maintain work-life balance, thanks in part to his new and (more) relaxed European lifestyle.

Stateside, pro and college coaching in all levels and all sports is an ultra-intense profession. Both NFL and college assistants and head coaches can find themselves spending more than 100 hours at team facilities, breaking down film, building out game plans, and analyzing players. So intense is coaching that longtime Baltimore coach John Harbaugh makes it his routine to sleep on his office couch during game weeks. Andy Reid, coach of the Super Bowl champion Chiefs, has talked of sleeping just three hours a night— and keeping index cards near him, just in case he comes up with a play in the middle of the night.

In Munich, Thomas gets to avoid such extreme schedules while still honing his craft as a position coach for the offensive line.

“You can tell that there is a PASSION for American football over here that’s really UNTAPPED.”

“Being in Europe, because these guys all have jobs or are at school during the day, it allows you to balance family and coaching a little bit better than if you were to take a college or a pro job here, where it would be your only job because of the time requirement,” Thomas says.

This doesn’t mean he doesn’t take games seriously: he’s quick to emphasize how excited he is to “coach adults in meaningful, serious games that are important to the city.” But the way his Munich players “commit” to football is different from NFL intensity, which pushes players to build their entire lives around training, film study, and recovery. “Some of the guys on [the Munich Ravens], they’ll work seven to five, and then get in their car or get on the train or drive for two hours to get here for practice that starts at eight o’clock at night,” Thomas says. “Then they get back in their car and drive home and get home at 1 a.m. and then go work the next day.”

That means Thomas has just a few hours (instead of a full workday-plus) to teach his players the game. This leaves plenty of time for the life Annie wants—the kids, now ages 11, nine, seven, and five years old, are enrolled in an international school and adjusting well to the experience. “We still have plenty of time to be with the family, see the kids, go on trips, do all the family stuff,” he says. “Being able to come over here and bring them for a short period of time… and still be part of the excitement in the family atmosphere that a professional team brings, and being able to take them to practice—I think was a really good balance.”

THOMAS PUT HIMSELF in position for this balance simply, with a phone call to the Ravens organization, according to Sean Shelton, Munich’s director of sports operations. And Shelton was more than happy to get an NFL superstar coaching his linemen. “This is something he wanted to do,” Shelton says. “We just tried to clear the path and help him with some administration tasks and work visas.”

In clearing that path, the ELF has allowed Thomas to channel his inner scout. He’s not working with top talents, or even clear NFL draft prospects, because the level of competition in the ELF (and Euro leagues in general) is far from NFL-level—and can’t even match big time college conferences. Thomas likens it to NCAA Division II football. “This is the same game of football that you know and love,” he says, “just with players that haven’t had the resources or experience to tap their full potential as the guys in the States.”

Nick Alfieri, who directed Unicorn Town, a Christian McCaffrey-produced documentary about the American import experience in Germany, calls the ELF “clearly the most talented and the most visible league” in Europe. “It’s such a broad range of players on the field, and certain positions are a little bit more talented than others,” he says.

The ELF may gradually help to improve that. Better funded teams could sign better import players (a.k.a., Americans), and while most leagues stipulate that only two are allowed to be on the field at the same time, in the past there were few rules dictating how many can be on a roster or how much they can be paid. Salary caps and a strict limit of four American players per team make the competitive field more level. ELF teams also solve another problem: It’s not uncommon for local players to quit showing up to practices and games due to outside obligations or even planned holidays, partly because, in other leagues, players actually pay “dues” to play. But the ELF pays everyone on the roster a small stipend. Already, both Alfieri and Shelton say the ELF has drawn talent from other leagues, which include the GFL (German Football League) and AFL (Austrian Football League), in which they each respectively played.

Thomas hosted a clinic for offensive line earlier this year in Munich.

Thomas is the other drawing card. “Recruiting with Joe Thomas as your offensive line coach makes my job easy,” Shelton says. His value will go far beyond name-recognition, in part because of the position he’ll coach. “Offensive line coaching in Europe is one of the poorest areas,” he says. Shelton recalls another American import coach from his time in Austria, Dan Morrison, who introduced drills and concepts that spread across American football throughout Austria, and hopes Thomas can have a similar effect.

Thomas understands the impact he can make, too. Munich’s roster has topflight athletes, he says. His job: Transform their natural ability into on-field production. “One of the things that was super-exciting for me is the talent over here, in pockets, is just as good as the talent you’d see in the NFL—but it’s just not developed,” he says.

One such player: Marlon Werthmann, who traveled to the US to participate in Wisconsin University’s Pro Day to perform for NFL scouts (where he pumped out 31 reps on the bench press, which would’ve tied for third most for his position at this year’s NFL Scouting Combine). The 6’4”, 290-pound lineman also had a workout with the Browns. Werthmann was part of the NFL’s International Pathway Program, a program meant to identify foreign-born talent for the league, in 2022. But it’s still worth noting that Werthmann’s chances to impress NFL scouts came with the Badgers and Browns, two teams Thomas knows well. “Working with guys that have huge potential and high ceilings like that is really fun for a coach, because you see rapid improvement,” says Thomas. If Thomas has his way, Werthmann will only be the first of many of his German acolytes to get a shot at the NFL. “If they’re given the right opportunity and the right exposure, I think there is going to be a little pipeline that develops.”

That pipeline may have underrated utility for the NFL in the coming years, offering up talent to the NFL while also pushing the league to develop its growing overseas audiences. “To be able to grow the game, make it more popular, you definitely need to tap into the international market,” Thomas says. “I think that if we’re able to get some players from the ELF that are European players that are able to become NFL players—I think that story is going to be really attractive and exciting to a lot of NFL fans.”

THOMAS’S COACHING START is not for all US-bred football pros. The pace of life can feel at odds with the strictly regimented nature of most American sports—and it remains to be seen whether it will prepare Thomas to potentially jump to the NFL of college coaching. But with every practice and game he coaches, and with every glowing comment about the ELF, he helps legitimize the league as an increasingly viable option for those who want to explore football careers without becoming wholly consumed by the game. “Joe can be an example and a demonstration that this can be a really cool experience—and not only a football experience, but a life experience,” Shelton says.

The ELF might not be a place to forge future NFL stars just yet—but there is momentum building, and more attention on an international league than ever before. Along with Thomas’ season-long stint with the Ravens, Miami Dolphins star receiver Tyreek Hill hosted a series of youth camps with ELF teams in Paris, Frankfurt, and Madrid in March. The ELF has signed more imports with high-level Division I, USFL/XFL, and even NFL experience than other leagues have in years past, according to Alfieri and Shelton.

As invested as he is in the game, Thomas doesn’t plan to become a Euro football lifer. After the season, he says, he’ll move back to Wisconsin. And who knows where his coaching career may land him after that? “We haven’t really made any plans beyond this season,” he says. “But you never know.”