Historic flooding possible as TS Debby bears down on southeastern United States

Not so little Debby —

Tropical rainfall and training bands, it’s going to be a soggy mess.

Enlarge / Satellite image of Tropical Storm Debby on Sunday morning.

NOAA

As often happens during the month of July, the Atlantic tropics entered a lull after Hurricane Beryl struck Texas and short-lived Tropical Storm Chris moved into Mexico. But now, with African dust diminishing from the atmosphere and August well under way, the oceans have awoken.

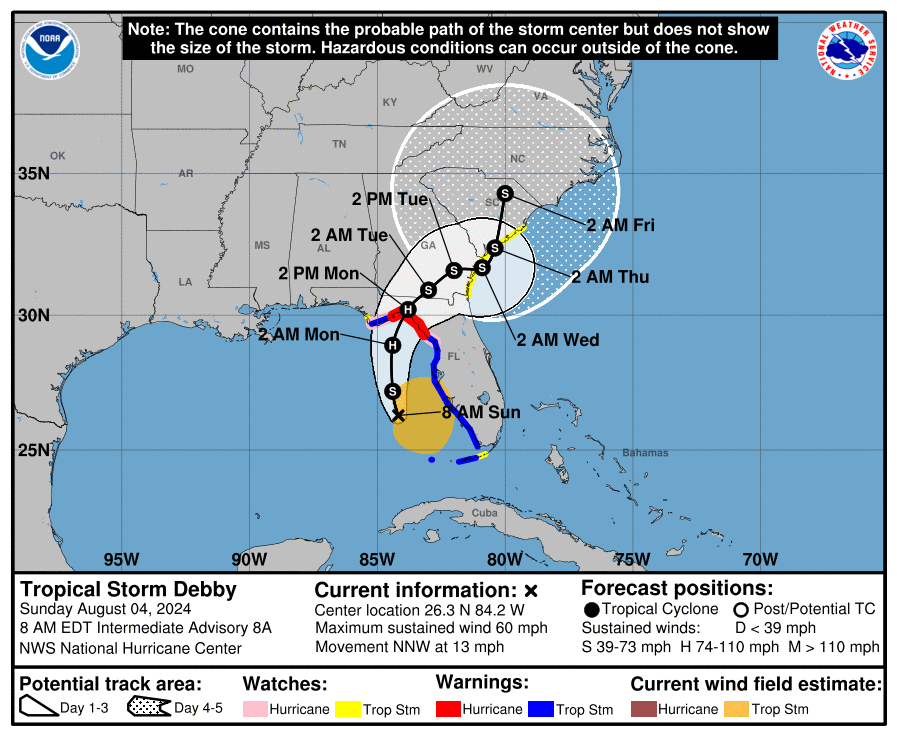

Tropical Storm Debby formed this weekend, and according to forecasters with the National Hurricane Center, the system is likely to reach Category 1 hurricane status before making landfall along the coastal bend of western Florida on Monday.

As hurricanes go, this is not the most threatening storm the Sunshine State has seen in recent years. Yes, no one likes a hurricane, or the storm surge it brings. But Debby is likely to strike a relatively unpopulated area of Florida, venting much of its fury on preserves and wildlife areas. This won’t be pleasant by any means, but as hurricanes go this one should be fairly manageable from a wind and surge standpoint.

Major flood storm expected

But there is a far larger threat from Debby that will unfold well into next week over the southeastern United States—a major flood storm. Historic flooding is likely in areas of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Debby is motoring along to the north-northwest at a fairly good clip as of Sunday morning, at 13 mph. This is a fairly common path for hurricanes as they skirt around the edge of high-pressure systems. Then, when they gain a sufficient amount of latitude—as Debby is now doing—they turn poleward and eventually move toward the northeast.

Debby is expected to meander next week.

National Hurricane Center

And this is just what Debby is likely to do through about Monday. However, after this time it appears that high pressure building over the central Atlantic Ocean will strengthen enough to block an escape path for Debby to the northeast. Should this occur, it will bottle up the storm in the vicinity of the Georgia and Carolina coasts for two or three days.

There remains a lot of uncertainty about just where Debby will go after striking Florida. Most likely it crosses Georgia on Tuesday and, then its center may reemerge into the Atlantic Ocean. Regardless, its center will likely be near, or just offshore. From there it will be able to tap into very warm seas, in the vicinity of 83 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

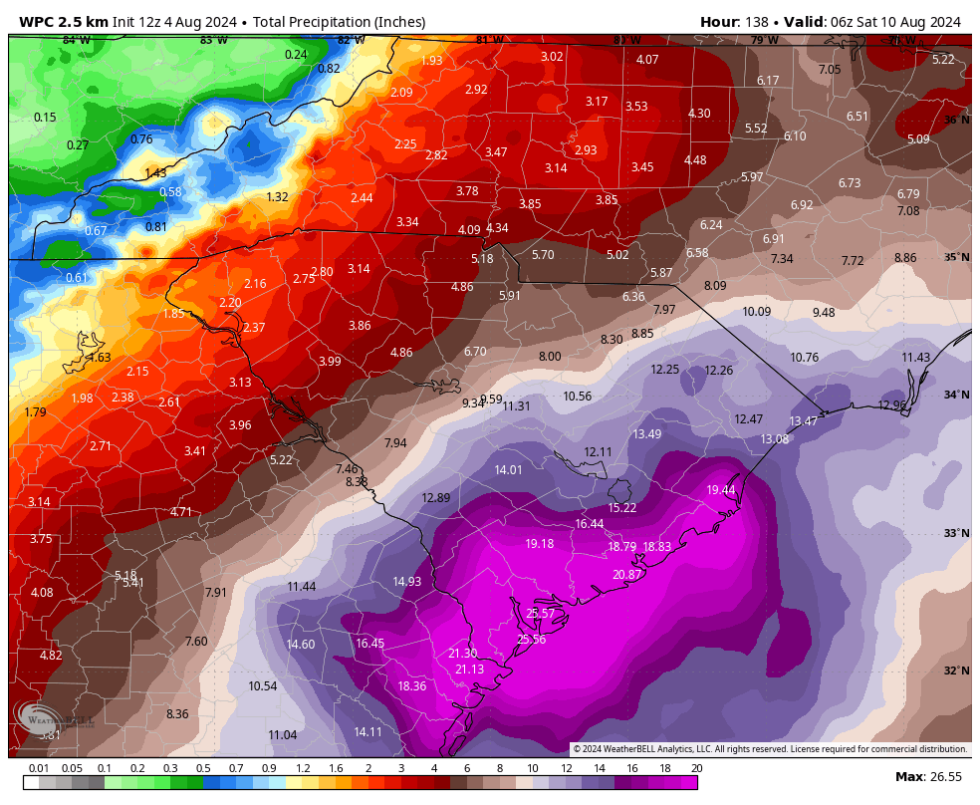

In such a pattern, with a nearly stationary storm, rainfall bands can be continually replenished by moisture drawn in from the ocean. This produces intense tropical rainfall and “training” in which a band of rainfall more or less comes to rest over a given area, fed by offshore moisture.

Because we are still a few days from this pattern setting up, and due to the uncertainty in Debby’s path, we cannot say precisely where the heaviest rains will occur. However the Weather Prediction Center, the arm of the National Weather Service tasked with predicting rainfall amounts, is forecasting some pretty staggering totals for the period of now through Friday.

Enlarge / Rainfall accumulation forecast for next week from NOAA.

WeatherBell

From Savannah, Georgia, north through Hilton Head Island and Charleston, South Carolina, the Weather Prediction Center is calling for accumulations of 20 to 25 inches, with higher totals possible in some areas. Moreover, it is possible that these high rainfall totals extend dozens of miles inland.

The African wave train gets rolling

Parts of Florida and North Carolina may also see extremely high rainfall totals over the next several days, due to the uncertainty in Debby’s motion.

And that is not all. As we get deeper into August, tropical waves are starting to fire off of the west coast of Africa. One of these is now approaching the Windward Islands, and should move into the Caribbean Sea next week. There, it has a chance of developing into a tropical storm, or more. This is likely the beginning of a period of frenetic activity characteristic of August, September, and the first half of October in the Atlantic tropics.

All of this is in line with expectations from forecasters for an exceptionally busy Atlantic hurricane season. This is due both to an anomalously warm Atlantic Ocean—seas fueled by climate change are at all-time highs in the modern era—and the imminent development of La Niña in the Pacific Ocean, which creates conditions favorable for the development of hurricanes in the Atlantic basin, which includes the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico.