Can you read this cursive handwriting? The National Archives wants your help

:focal(1000x752:1001x753)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/32/94/3294bdbb-bd00-4fc7-8ab3-88faf17855d7/cursive.jpg)

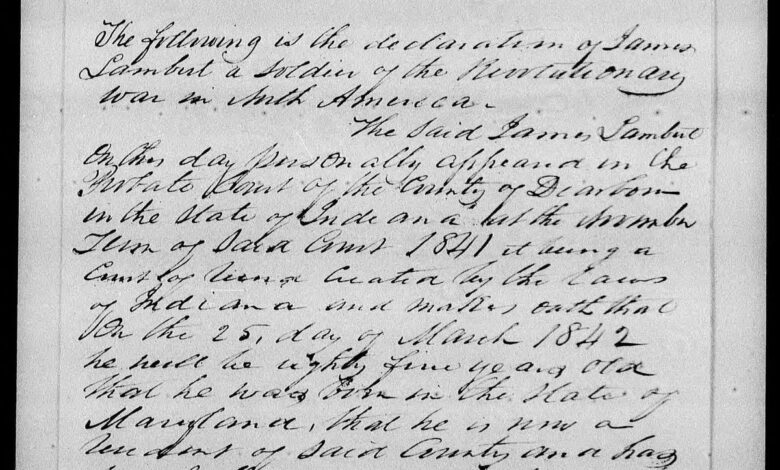

A Revolutionary War pension and bounty land warrant application submitted by James Lambert

National Archives

The National Archives is brimming with historical documents written in cursive, including some that date back more than 200 years. But these texts can be difficult to read and understand— particularly for Americans who never learned cursive in school.

That’s why the National Archives is looking for volunteers who can help transcribe and organize its many handwritten records: The goal of the Citizen Archivist program is to help “unlock history” by making digital documents more accessible, according to the project’s website.

Every year, the National Archives digitizes tens of millions of records. The agency uses artificial intelligence and a technology known as optical character recognition to extract text from historical documents. But these methods don’t always work, and they aren’t always accurate.

That’s where human volunteers come in. By transcribing digital pages, volunteers make it easier for scholars, genealogists and curious history buffs to find and read historical documents.

Getting started is easy: All you need to do is sign up online. The free program is open to anyone with an internet connection.

“There’s no application,” Suzanne Isaacs, a community manager with the National Archives, tells USA Today’s Elizabeth Weise. “You just pick a record that hasn’t been done and read the instructions. It’s easy to do for a half hour a day or a week.”

If you’re not confident in your cursive deciphering skills, the National Archives has other tasks available, too—such as “tagging” documents that other volunteers have already transcribed. Tagging helps improve the searchability of records.

Already, more than 5,000 volunteers have joined the Citizen Archivist program. Many are hard at work on “missions,” or groups of documents that need transcribing and tagging. For example, current missions include Revolutionary War pension files and employee contracts from 1866 to 1870.

The Revolutionary War mission, which kicked off in June 2023 in partnership with the National Park Service (NPS), includes files connected to more than 80,000 veterans and their widows.

“The pensions are revealing the stunning—frequently heartbreaking and sometimes funny—complexity, nuance and previously unknown details about the American Revolution and the nation in the decades after,” says Joanne Blacoe, an interpretation planner for the NPS, in a statement. “It’s rich content that will benefit [national] parks and inspire artists, researchers and families connecting to ancestors.”

Volunteers can spend as much or as little time as they want transcribing and tagging. Some participants have dedicated years of their lives to the program—like Alex Smith, a retiree from Pennsylvania. Over nine years, he transcribed more than 100,000 documents, as WTOP’s Kate Ryan reported in March 2024.

“I was looking for something to give purpose, and could give some structure to my retired life,” he said. “It was just perfect.”

For Smith, the transcription work is also a chance to peer back in time and connect with Americans of the past. He’s been surprised by some documents, like a note inviting Gerald Ford to join the Green Bay Packers, and moved by others, like Civil War pension records.

“You’re seeing people in desperate straits,” Smith told WTOP. “They’re trying desperately to get some reasonable pension paid to them, and you think, ‘These are individual tragedies.’”

Though cursive instruction was once standard, today’s educators and lawmakers are divided: Should schools emphasize penmanship or keyboard skills? But even as laptops, tablets and other devices become more ubiquitous, cursive is making a comeback. More than 20 states now require schools to teach cursive, according to Education Week’s Brooke Schultz.

In California, a law mandating cursive instruction took effect in January 2024.

“For some students, it’s a great alternative to printing, and it helps them be more accurate and more careful with the writing,” Erica Ingber, principal of Longfellow Elementary School in Pasadena, told the Los Angeles Times’ Howard Blume last year. “And then for others, it’s just another thing that is difficult for them.”

A few months later, another law requiring cursive instruction passed in Kentucky.

“We don’t want this to become a lost art,” Sean Howard, superintendent of Kentucky’s Ashland Independent School District, told WSAZ’s Abbey Lord in August 2024. “There is research that connects the ability to read and fluency … to the ability to write cursive.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.