Cheesecake with the Heavyweight Champ

Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton didn’t agree on much. But years before Burr put a bullet in Hamilton’s stomach, they had complete solidarity on at least one issue: They both thought a Dutch secondary school in the growing city of Brooklyn was an excellent idea. They were the only Founding Fathers who supported and contributed to the construction of Erasmus Hall Academy. Erasmus opened its doors of higher learning in 1786. In 1904, the school was greatly expanded, and Erasmus Hall Academy became Erasmus Hall High School.

Countless notable people attended Erasmus Hall over the years. There’s a list of more than a hundred alumni who went on to outstanding careers. My time as an actor and comedian got me on this list but with an asterisk. I’m the only one who has “did not graduate” next to his name. I’m sure Alexander, Aaron, and even Desiderius would not be too happy with me. Legendary looney chess champion Bobby Fischer has a “dropped out in 1960.” At least that has some specificity to it. Like maybe he just didn’t need school anymore. My “did not graduate” seems to suggest “That’s all we’re saying about this guy.” Celebrities were not subjected to the same scrutiny in the 1970s. So the irony of me playing a high school teacher on a successful sitcom (Welcome Back, Kotter) despite being a high school dropout was never discovered.

In the mid-1970s, Kaplan co-created the sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter, inspired by his own high school experiences. Kaplan (above, center) starred on the show as a teacher who returns to his alma mater and tries to educate a group of unruly students known as the Sweathogs.

People generally quit school for one of three reasons: financial need, incorrigibility, or a learning disorder. None of these applied to me. I had two interests in life, and school wasn’t one of them. My first interest was baseball. Baseball was very big in Brooklyn.

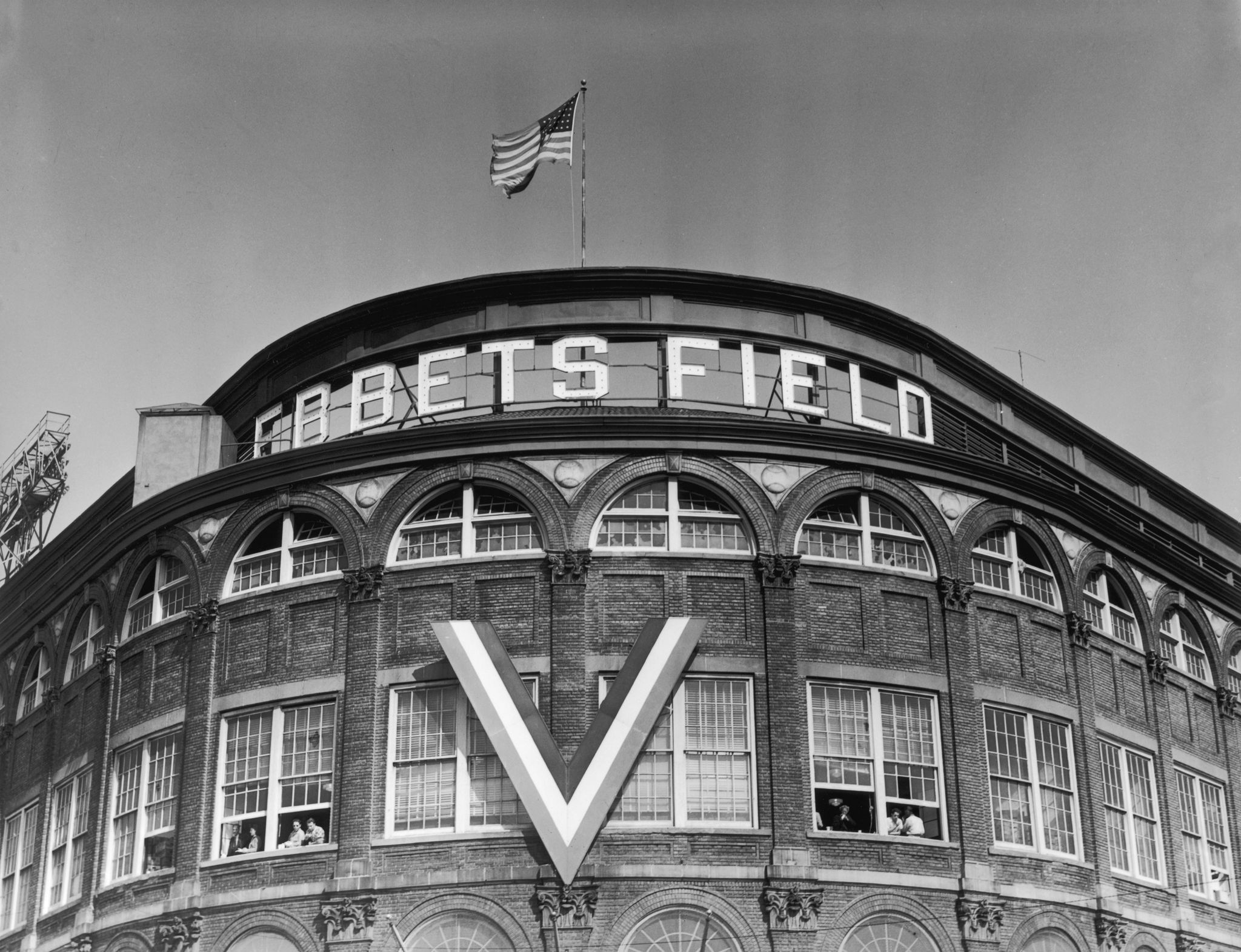

Ebbets Field, the home of the Dodgers, was the smallest ballpark in the majors, with less than two thirds the capacity of Fenway Park, the next smallest. But when times got sketchy between 1939 and 1945 thanks to Hitler, tiny Ebbets Field led both leagues in attendance. Brooklynites could do without almost anything—except baseball. I lived a block away from Ebbets Field and knew it like the back of my hand. I loved everything baseball—watching it, talking it, and especially playing it.

I started playing at a huge dirt lot right behind Ebbets Field. It was used for Dodger parking, but when the team was out of town, it was transformed by local kids into two or three baseball fields. We called it “Little Ebbets.” The games were really competitive, especially between teams from different neighborhoods, and tempers could flare. “I ain’t out! I nick da ball, ya Greenpoint dipshit.” I later advanced to playing in pickup and arranged games at a more civil place called the Parade Grounds, a forty-acre recreational area in the middle of the borough that specialized in baseball. There were all levels of games there and I played whenever I could, biding my time till I could try out for the Erasmus team.

Early in my sophomore year, I went into Erasmus baseball coach Austin Dugan’s office and enthusiastically asked for a tryout. Dugan had previously coached football and must have thought he could spot an athlete. Based on my appearance, he surmised that I didn’t fall into that category. With a faint smile, he asked if I could hit like Duke Snider and field like Pee Wee Reese. I said, “No” and that was that—no tryout. I guess he wanted me to say, “I could leave both of them in the dust,” but he didn’t make me very comfortable. I don’t know if I would have made the team (they were good that year), but not getting a chance was a major downer.

The rotunda at the entrance to Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. Kaplan grew up a block away from the ballpark.

A.D. (after Dugan), I continued to play at the Parade Grounds and my game improved steadily. By the next year, Dugan had heard about me and asked me to come to his office. I must have passed the jock-looking test this time, because he encouraged me to try out. But our timing was off. At that point, my grades weren’t good enough and practicing every day would have interfered with my other pastime.

My second big interest besides baseball was gambling. I was a good card player and there were plenty of poker games going on, mostly with guys who were slightly older than me. I was skilled at watching bowlers compete and figuring out who would come out on top. This was a popular form of gambling at the time in New York. It was called “action bowling,” and basically it was people bowling for money and other people watching and betting as well. It could be individuals or two-man teams in action.

I had developed my betting skills at the bowling alley run by Freddie Fitzsimmons. Fitzsimmons was a major league pitcher, coach, and manager as well as an avid bowler. He pitched for “Dem Bums” for eight years, and with some of the money he received from the Dodgers, he decided to open an alley next to Ebbets Field. There was always plenty of action bowling going on at Fitzsimmons. I was introduced to it at the age of twelve.

Four or five nights a week, I was either playing cards or traveling to some bowling alley.

After a few years and a rough start, I got to know my way around the action-bowling scene. By sixteen, I was totally immersed in it. Several bowling alleys were known as “action houses.” Ave M Bowl in Brooklyn was on top of the action hill. It was owned by a guy they called “Fishface.” There was nothing fancy about Fishface or his bowling alley, but that’s where the greatest action was. Ave M was packed every night and there were always multiple matches going on. These could be prearranged, sometimes featuring well-known bowlers, even guys who had bowled on television. However, most games were negotiated on the spot. Just great bowlers who hailed from everywhere, looking to gamble. The negotiations could be quick and easy or sometimes get testy. “I need a ten-pin spot from you.” “I’ll spot you all you can eat.”

The stakes were usually anywhere from twenty dollars to a thousand. Generally, the bigger the game, the more attention it attracted. A really big match could have fifty people watching and betting. Four or five nights a week, I was either playing cards or traveling to some bowling alley, and every weekend, weather permitting, I was at the Parade Grounds playing baseball. I had zero interest in or time for homework. My poor parents couldn’t handle me. They were older and struggling to get by. My grades got progressively worse, and I quit school late in my junior year.

I was totally blind to the big picture, and quitting school didn’t seem like a major deal. I joined Vic Tanny’s (a peer of Charles Atlas) new gym, which was right next to Erasmus. I would take the bus with kids I knew and later have lunch with them. They were studying for the SATs and concerned about getting into the best possible colleges, while I was concerned about whether “Doug the Rug” would out-bowl “Armenian Pete” that night.

Before long, I started to drift apart from this school group and was basically alone most of the time. I desperately wanted to meet a girl to ease the loneliness. Sometimes, on the weekends, after playing baseball and before hitting the bowling alleys, I would go to Flatbush and Church avenues. Scores of Erasmus students would walk around in groups, just hanging out. One night I’m standing there with some ex-classmates when two very attractive girls walk by. They’re dressed a little more provocatively than your average “Flatbush and Church” females.

One of the guys says, “You don’t look like Erasmus girls, much too sexy.” Strangely, they stop. What, they’re stopping? What is happening? This was not the protocol; girls who looked like that didn’t stop.

One of the girls immediately started talking to me; she shifted her amazing body to block out everyone else. Maybe all those afternoons at Vic Tanny’s were finally paying off. After fifteen minutes, we had a date for the next night. It was easy peasy. She gave me her address and bus information. My guys looked at the information and offered their knowing analysis: “Girls from that part of Brooklyn all put out. They like to have sex and then never see the guy again.”

I’d had sex once and was very ready to try again. But I was a little torn. I wanted to make this more than a one-time wham, bam, thank you, Sam arrangement. This could be something great for me.

What should I wear? It was a Saturday night, so I figured a sport jacket would be in order. That morning, I went to Abraham & Strauss, a big department store in downtown Brooklyn. I sprung for one of the top items in the men’s department, a double-breasted blue blazer that cost the unheard-of price of sixty dollars. The salesperson also talked me into a shirt and a gold pocket square to match the buttons.

When I got off the bus, her neighborhood looked really interesting; it had the same kinds of apartments as mine, but everything was more varied: the stores, the smells, the sounds. It was more alive. It almost felt like another city. I rang the bell and got buzzed in. She looked even better than the night before. If she wanted sex, no way I could not oblige. Forget about “Will you still love me tomorrow?” I was suddenly okay with “a moment’s pleasure.”

She said, “Come in and meet my parents.”

There they were, sitting on the couch with big smiles. They stood up, her father shook my hand, and her mother grabbed her husband’s arm and asked, “Weah you kids off to?” I looked at the girl and said, “See a movie?” She said, “Sure.” And we were on our way.

I was with a beautiful girl, her parents seemed to like me, and it was a perfect evening. This was really happening.

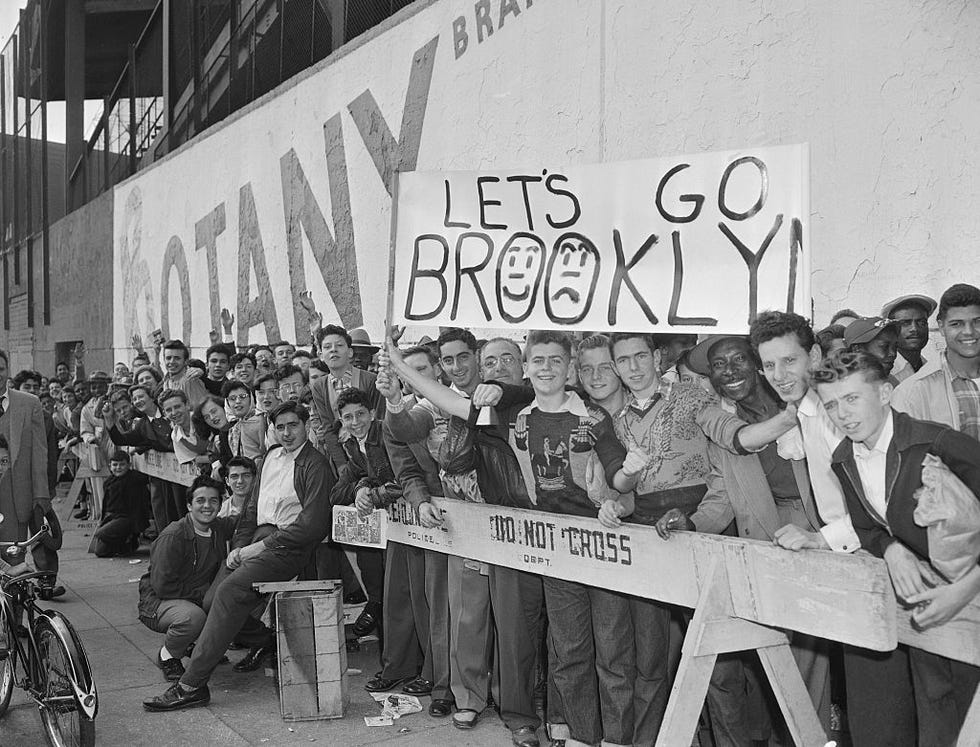

A crowd of Brooklyn fans outside Ebbets Field before a game with the rivals Giants.

When we got downstairs, I asked what movies were near her house. She didn’t answer till we walked around the corner. Here it comes; she’s going to say, “Do we have to go to the movies?” I’m going to answer, “What would you rather do?” She’s going to shove her amazing body against mine, kiss me, and say, “I want to ‘ball,’ ” which meant “hook up” in 1961.

I might have been good at reading card players, but I was way off on this. As soon as we turned the corner, she faced me and coldly said, “We’re not going anywhere; I have zero interest in you.”

I couldn’t have heard that right. She couldn’t have made me travel halfway across Brooklyn to tell me that. One look at her face told me it wasn’t a joke. My perfect evening vaporized. I couldn’t move or say anything. She continued her assault. “What are you, dumb? Did you hear me? Leave!!!”

Two older, leather-jacketed greasers were waiting for us. They walked over and one said, “Listen, kid, forget about this; you didn’t do anything wrong. Just go home.” She tried to insult me again and he stopped her. He gave me a little dignity and I walked away. He was obviously her boyfriend, and I assumed her parents had given her an ultimatum about him, so she went to Erasmus searching for a presentable nebbish.

I didn’t follow instructions to go home. I went to the movie I would have probably taken her to, and after that I went to a restaurant in this interesting neighborhood. There was a buffet. I had no concept of what kind of food it was but kept stacking my plate, trying to eat away the devastation. Nobody had any idea who I was. I was a well-dressed mystery kid with weird hair (a pre-Afro, shapeless, unruly clump). I was eating alone and I got a lot of curious stares. People were paying attention to me. This was fun, and it eased the pain of being dumped.

I was done with women. They could keep their phone numbers that they weren’t going to give me anyway. I started to work out even harder, spending long days at the gym. My father said, “Stop already. You’re starting to look like a lumberjack.” Just to have something to do on weekends, I repeated the events of that faithful night (minus the dumping). I’d get a new outfit and travel to different parts of Brooklyn. I would spend some time exploring neighborhoods that I had never seen, then be off to a restaurant on my own—I always got the stares—followed by a local movie. I wound up with four new jackets. My parents were sure I had a non-Jewish girlfriend that I wasn’t telling them about. “It’s okay—let us meet her.” My married older sister thought I might be gay. (“All those bodybuilders are.”)

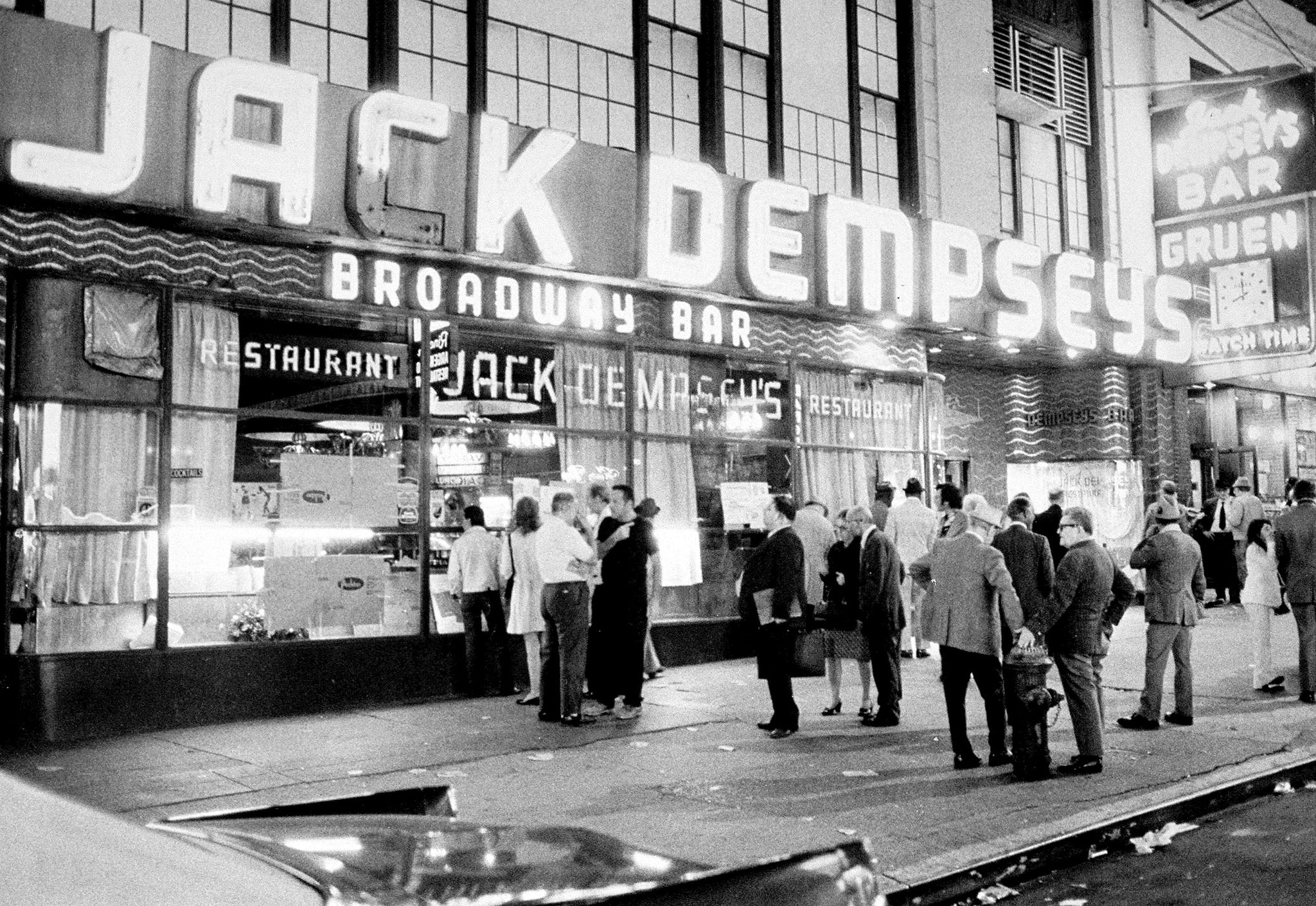

Jack Dempsey’s restaurant in the Brill Building on Broadway between Forty-ninth and Fiftieth streets in New York City. Dempsey, a former heavyweight champion boxer, ran his restaurant from 1935 to 1974. It was famous for its cheesecake.

After a while, I got bored with Brooklyn, so I stepped it up and started going into Manhattan. If you were from an outer borough, this was a big deal. Your heart started pounding a little when you got on that express train to “the City.” The restaurants were better and the movies were first-run. I was done buying jackets and satisfied myself now by just wearing a weird tie to garner more attention. I’d take the subway to Forty-second Street, usually eat at a quaint place somewhere between Sixth and Ninth avenues. I never knew where I was going and loved the happenstance of just finding a restaurant.

One Saturday night, I walked up Broadway to Forty-ninth street, which was close to the movie I was planning to attend, and saw former world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey’s restaurant. It looked much bigger and more commercial than my usual choice, but I decided to try it. I liked boxing and had fond memories of eating ice cream and watching boxing with my dad. I had seen Dempsey a few times on TV, once when he was the subject on This Is Your Life, my mother’s favorite TV show.

I walked in and the maître d’ looked like he was expecting my parents to come in behind me. I uttered my now-familiar “One for dinner.” After a moment, he said, “Okay, follow me.” It was early and the restaurant was pretty empty.

My Brooklyn-Italian waiter came over with a smile on his face and asked where my girlfriend was. I said I was in between women. He said, “No wonder, with that tie.” We both laughed and he said, “You’re smart. Women are nothing but aggravation.” I said, “I know, us guys are all so easy to get along with.” He said, “Who are you, Benedict Bernstein?” I could tell this was going to be a fun meal. I asked him what was good. He said, “Whatever you like, it’s all good.” I ordered and during the meal we talked a little more and had a few more laughs. I did my Lawrence Welk and JFK impressions for him; he told me about his two sons.

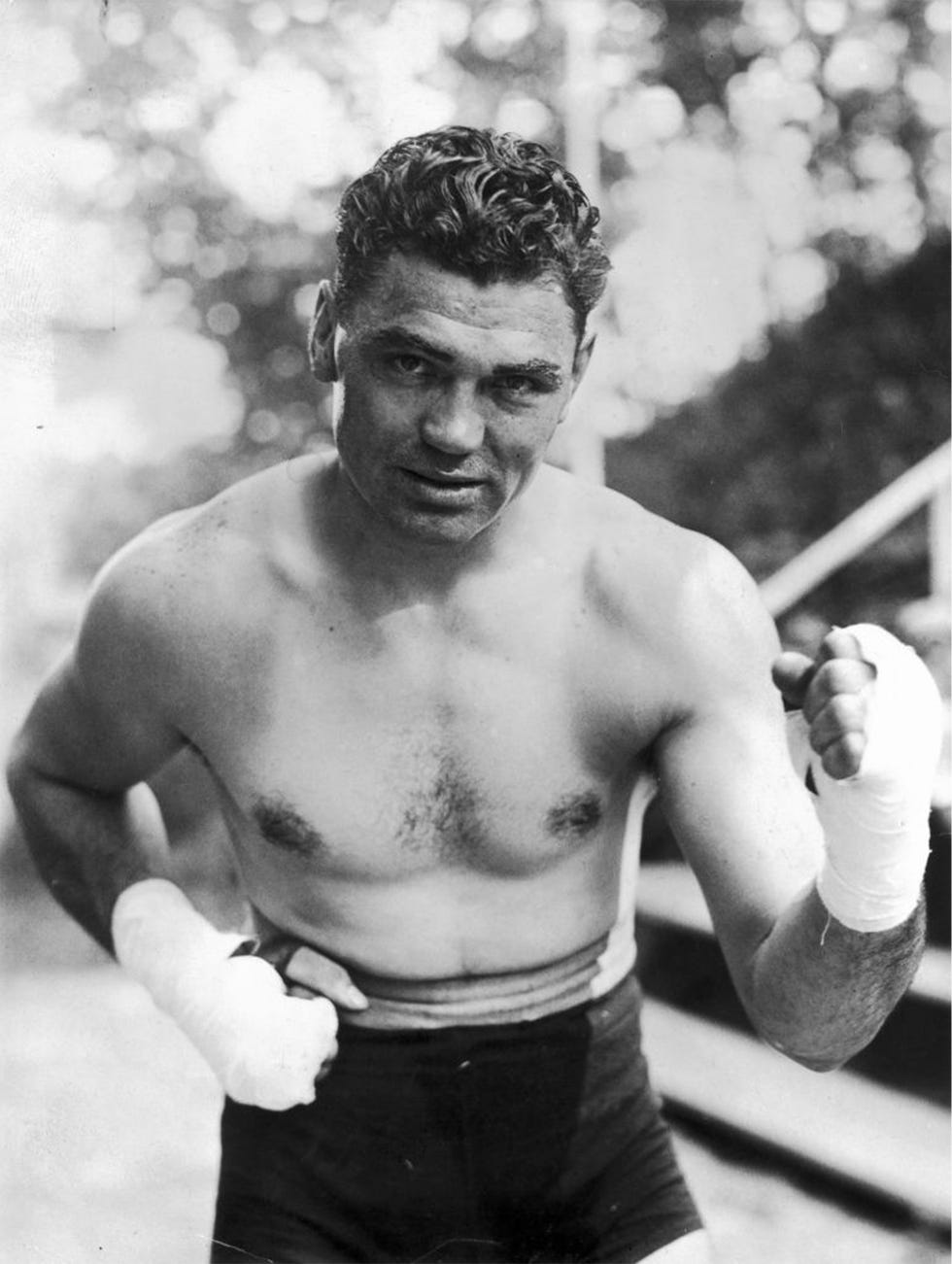

I saw Jack Dempsey walking around and greeting early dinner arrivals. He’d been one of the most feared boxers in ring history. (His nickname was “the Manassa Mauler,” after the Colorado town where he was born, and he was indeed a brute when he fought.) But right now he seemed like a big, genial old guy. I really liked everything about this place. Maybe it was the waiter. Maybe it was Dempsey’s presence and the boxing memorabilia. Or maybe I wasn’t really a boutique-restaurant guy after all.

Jack Dempsey, who was born in Manassa, Colorado, was a fearsome fighter and held the title of heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926.

Two weeks later, I asked myself out on another date and I was back at Dempsey’s; I wore a regular tie and that blue blazer from my ill-fated date. I was shown to the same table and had the same waiter. He was happy to see me but a little busier, so I skipped the small talk and just ordered. I was waiting for my meal when I felt a presence at my table.

I looked up and saw Jack Dempsey standing beside me. “Hi, young fella.” He stuck out his hand and said, “Jack Dempsey.” I stood up, shook hands, and introduced myself as Harold, my given first name. He said, “Good to meet you, Harold—fine jacket you got there. Can I join you for a minute?” I said, “Yes, of course.”

Boxer was slightly below shepherd on my list of possible career choices.

He said, “You really impressed your waiter. He thinks you’re a fine boy.” So far, fine seemed to be his favorite word. Dempsey continued, “I noticed you when you came in before. We don’t get any young fellas your age coming in alone. When you came back tonight, I took a good look at you and knew what was up.’’

Say what? He took a good look at me? He knows what’s up? Has this boxing legend somehow figured out that I’m a high school dropout who goes out solo to movies and restaurants? Kid Blackie (another one of his nicknames) leans in and hits me with “You want to be a fighter, don’t you, Harold?”

Now, boxer was slightly below shepherd on my list of possible career choices, but this world-famous individual was giving me a chance to play a role other than sad, lonely mystery kid, and I jumped at the opportunity. I instantly said, “It’s always been my dream.”

His face bore the results of one hundred or so professional fights, and there was a glaze to his stare; he talked very fast and he was very serious. “Harold, nobody knows what you’re feeling better than me, but I got to tell you this: Nine out of ten guys that want to be fighters, they wind up with nothing but broken dreams and broken noses. Now, I have never seen you fight and you might be really solid, but I got to start out by telling you that.”

He waited a second and then continued, “Where have you fought?” I said, “The Flatbush Boys Club.” I’d never been in the place, but I’d heard there was boxing there. He nodded and continued his rapid delivery. “Now, if you want, I can give you the name of a guy to go see; he’ll work you out and see what you got.”

In distinguished company at Jack Dempsey’s restaurant in 1935. From left: Gene Tunney, the boxer who defeated Dempsey to take his heavyweight title in 1926; Bernard Gimbel, the president of Gimbels department store; the writer Ernest Hemingway; and Dempsey.

I said, “All I want is a chance, Mr. Dempsey.” I thought of baseball coach Dugan and said the line convincingly.

Dempsey liked my response. “Now, if this man happens to think you got everything it takes—now, mind you, that’s a long shot—but if he says that, I’ll help you where I can.” I nodded. He continued, “Now, if boxing is not the right ticket for you, you have to find out what is.”

He stood up. “Well, you go over there and we’ll see what he says. Enjoy your dinner and keep dressing like a gentleman.”

This legend, a genuinely nice man, was going out of his way to help a total stranger, who he mistakenly thought was a kindred spirit. And my response was to drag him into my fantasy world. How could I do something like that? What was wrong with me? To make things worse, at the end of the meal, my waiter came over with a piece of the restaurant’s famous cheesecake, compliments of Mr. Dempsey. He said sotto voce, “Enjoy it. Free cheesecake doesn’t happen here too often.” I picked up the name of the gym and the trainer on my way out, and I left feeling guilty and miserable. I never went to Jack Dempsey’s again.

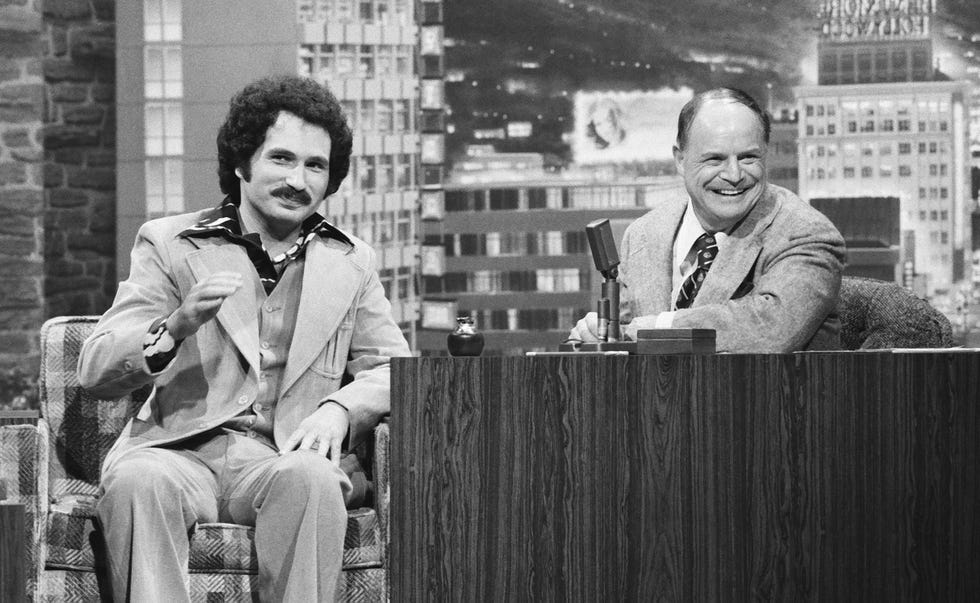

Kaplan during an interview on The Tonight Show with guest host Don Rickles in 1975.

But a guy like Jack Dempsey taking an interest in me prompted a self-evaluation. Why did I quit school? What was the right ticket for me? Would I ever meet a girl who liked me? I cut back on gambling and working out and started going to big dances at hotels in “the City” featuring famous bandleaders like Tito Puente. I had greater confidence, and pretty soon I met a few women. No more solo dinners. I tried out for a few minor league baseball teams. I never made it, but it coincidentally led me into comedy. (A story for another day.) It all got triggered by my one-minute meeting with the Manassa Mauler.

Early on in my showbiz career, I had an agent whose office was in the same building as Jack Dempsey’s. Sometimes the champ would be sitting at a table by the window. I’d walked by more than once but never caught his eye or went in to talk with him. After my first few appearances on TV, I decided the time was right to go back and tell him the whole story. “Mr. Dempsey,” I’d say, “I’m Gabe Kaplan. Do you remember talking to Harold, a kid from Brooklyn, and you thought he wanted to be a boxer? Well, here’s the real story.”

Unfortunately, Jack Dempsey’s closed before I got the chance to thank him for the advice and the cheesecake. Without that night, I don’t know where I’d be now. Maybe still in a bowling alley in Brooklyn. Or maybe dressed like a gentleman—but probably not.