Discover the Creative Power of Transposing on Guitar

Just as there are many reasons to change the key of a song—vocal range, chord form preferences, collaborations with horn players, or tone quality, for example—there are also many effective methods for transposing. Some electric keyboards have a transposing switch that allows the player to perform in their favorite key (like C) while adjusting the sound to match any other key. Guitarists have a similar tool: capo three frets up and play in the comfort of the key of G, and it will sound in the guitar-unfriendly key of Bb. Or, simply tune all the strings down a half step and turn those key of E chords into the key of Eb.

While these shortcuts are useful in a pinch, there is value in learning to play songs in different keys by actually transposing and learning the resulting chords and melodies. Chord voicings can be challenging but rewarding when you create arrangements that take you out of your comfort zone and reveal rich harmonies inherent to a particular key. Here’s how to do it.

Count the Steps

Let’s say you find a lead sheet or chord chart for a song you want to play, but it’s in the key of F—often tricky for acoustic guitar. You can easily transpose it to the easier key of G by counting steps. First, think of F as 1, since it’s the first note or chord of the key of F. Next, count the number of steps from F to G, the first note or chord of the new key. It’s one whole step, or two frets.

Now, change every chord in the song by that same interval. For example, if the song’s chord progression is F–Bb–Gm–C7–Dm, in the key of G it becomes G–C–Am–D7–Em. Each chord moves up a whole step, maintaining the same progression, just higher.

Apply the same method to the melody notes so they fit the new key. Singers, lead guitarists, or any melody instrument players will need to adjust their notes up a major second to be in the key of G.

Go the Shortest Distance

Now that you’ve transposed the song to the key of G, you might want to try it in E. The arrangement of notes and chords on the guitar, including open strings, can create unique sounds. Transposing might even make melody notes more accessible while you are playing chords. To experiment in E, count the interval between 1 in the key of G and 1 in the new key of E. (The 1 is always the note that shares the name of the key.) This time, it’s a major sixth. If you count the notes in the G scale—G A B C D E—you’ll see that E is a major sixth above G. Move each chord up by a sixth: in our example, the progression becomes E–A–F#m–B7–C#m.

Alternatively, you could transpose down by a half step from the original key of F, since E is one half step lower than F. The chords in F (F–Bb–Gm–C7–Dm) become E–A–F#m–B7–C#m.

Number the Chords

Another method for transposing involves recognizing the function of each chord within a key. (For more on that, see the November/December 2024 Here’s How, on the Nashville number system.) A common chord progression found in songs like George Gershwin’s “I’ve Got Rhythm” and Pete Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” is known as I–vi–ii–V. If you can quickly identify these chords in any key, transposing becomes much easier.

Instead of counting intervals, identify the function of each chord in the original key and assign it a number. For example, the beginning of “I’ve Got Rhythm” in the key of C has the chords C–Am–Dm–G7, which follow the I–vi–ii–V progression. The chords are built on the first, sixth, second, and fifth notes of the C major scale (C D E F G A B). To transpose the song to the key of G, simply apply the same I–vi–ii–V structure to the G major scale (G A B C D E F#): G–Em–Am–D7. Remember, the first note in the scale is always numbered 1.

Looks Aren’t Everything

If you find a song in the key of A, it might seem like a relatively easy key to work in, and the idea of transposing it to Bb can be off-putting. But here’s the catch:

in A, the chords might be something like A–G#m–C#7–F#m–B7–Bb7–A, as shown in Example 1. That’s doable, but it’s not your typical A–D–E progression.

There are good reasons for transposing to a more difficult key. It might allow for creative chord voicings, using open strings for added tension or color. By moving each chord up a half step, you can build new chords that offer access to richer sounds.

It’s important to maintain the same chord qualities: major chords stay major, minor chords stay minor, and so on. But you can experiment with enhancing them, as illustrated in Example 2, where the chords are: Bb6–Am9–Dadd4–Gm11–C7–B9–Bb6.

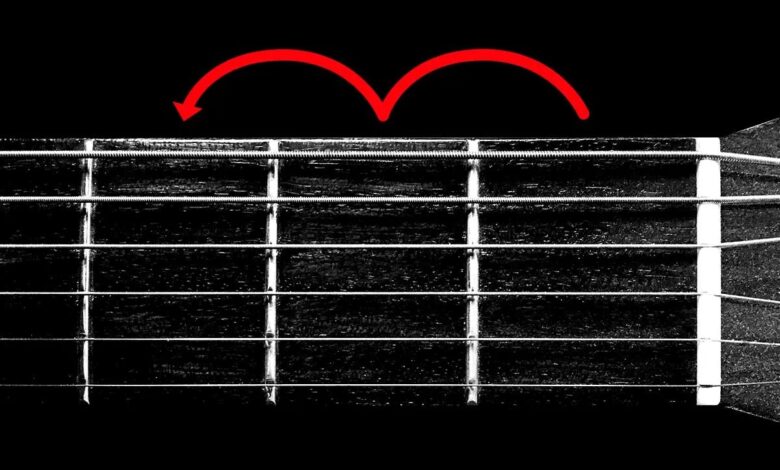

Adding the sixth to the Bb major triad creates some interest while still fitting well in the progression. As luck would have it, the open G string provides that note, making it easy to get in and out of in time. We then have the opportunity to use a familiar trick used by Neil Young, Paul Simon, and others: moving a C triad up a whole step (two frets) to get the Dadd4 chord. Gm11 might sound like it will be harder than Gm, but it turns out to be easier to grab while adding some beauty. Finding gems like this within chords of keys we might have wanted to avoid is just one of the things that makes the art of transposing worth learning and practicing.