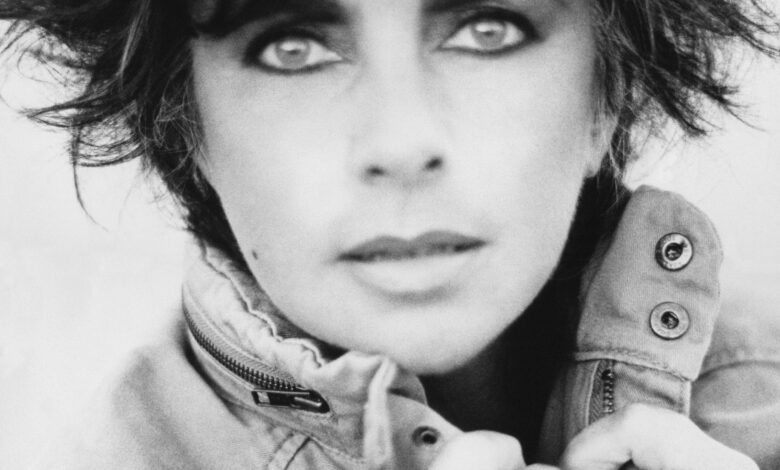

From the Vogue Archives: An Unmissable 1987 Interview With Elizabeth Taylor

“An Unmissable 1987 Interview With Elizabeth Taylor,” by Anne Taylor Fleming, was originally published in the October 1987 issue of Vogue.

In 1987, Elizabeth Taylor was ready to talk. Ahead of the release of her book Elizabeth Takes Off: On Weight Gain, Weight Loss, Self-image and Self-Esteem, the actor and advocate sat down with Anne Taylor Fleming to catch the world up–on her sobriety, her singledom, and her fearless dedication to the HIV/AIDS fight with her charity amfAR. The interview, in its entirely, below.

Americans like their movie goddesses larger-than-life, and Liz Taylor, ever since she was twelve years old, has obliged. “Let’s face it,” she says, “I was a freak.” Today, however, the star of our tabloid fantasies is back— in a daring new role—activist in the fight against AIDS, sober alcoholic, entrepreneur, author, single woman, and a radiant beauty, even more so at fifty-five than ever before. The question is, are we ready for Liz Taylor, feminist heroine?

Elizabeth Taylor is amused at the new perception of herself as a heroine. Not unflattered, she says, but amused. Once dismissed as a caricature of the grande dame lurching self-destructively from man to man and movie to movie, she is now luminously rejuvenated, respected for her openness about her private fight to be sober and slim, and her public commitment to the fight against AIDS. Taylor’s transformation has been dramatic and hard-won; along the way, she has made rooters of us all. She has the uncanny knack to make us forgive her appetites, her flagrancies—almost grudgingly admire them because they’re so big, so broad, and because they remind us that, icon or not, her life is no less messy than the rest of ours. And when she feels good, as she does now, we feel good, charmed by her survival and by the palpable, almost girlish enthusiasm she evidences at being in one piece and back on top. Here is no victim, no dupe of men, no tragic heroine à la Marilyn Monroe; here is a vital, sometimes bawdy woman who talks about herself with a self-deprecating candor and humor.

“You bitch,” she says to me, violet eyes flashing amusedly when I tell her I’ve spent half the previous night reading Kitty Kelley’s tell-all book about her. “You absolute bitch.”

She’s smiling and she looks terrific—fiercely tan but seemingly unlined—though she emphatically denies she’s had any cosmetic surgery, no facelifts, nothing. “Absolutely not,” she says when asked. “In losing all my weight [something like sixty pounds since she quit drinking in 1984], I lost the fat and bloat that hadn’t exactly helped my features, either in my face or body. Exercise helped tremendously. You’ll be able to read all about my transformation in my book, Elizabeth Takes Off: On Weight Gain, Weight Loss, Self-image and Self-Esteem, which will be published early next year.” (Taylor also has a new perfume, “Elizabeth Taylor’s Passion.”)

We’re sitting in the living room of her home, which curls around an outdoor pool in the expensive foothills of Bel Air. There are lovely French Impressionist paintings on the wall and, in a nearby room, discreetly framed family photographs on the tables, including some of her six ex-husbands, about whom she doesn’t wish to talk, I’ve been forewarned. This is the new role, the new incarnation; this is Elizabeth Taylor sober and solo. “This is the longest I’ve been single in my adult life,” she says, “but I’m not looking to get married. That’s a difference; I always needed a man in my life. Now, I enjoy the time alone, the quiet moments. I enjoy being introspective. This is a growing stage for me. I’m learning to leave myself open and be receptive to new things. I think I have an inner peace which is evolving. I’m very happy right now. I’m sort of beginning to grow up.”

Part of that growing up is her outspokenness about AIDS and her involvement with AmFAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, for which she is national chairperson and major fundraiser.

“But I’ve always been pretty outspoken,” she says, “always taken risks. I remember once, when I was fifteen, and under contract to MGM, Louis Β. Mayer had insulted my mother and I told him, ‘You and your studio can go to hell.’ They all came after me and told me I should go back in and apologize to him. I said, ‘He’s the one who should apologize to my mother.’ I never did go back in. But nothing happened; I wasn’t fired and the only reason was because I was in demand. I knew that. I already knew who I was, and I knew the phoniness of this town.”

“That phoniness is partially what prodded Taylor into the AIDS fight. Asked in 1985 to sponsor a big dinner for APLA (AIDS Project Los Angeles), it took her seven months to get enough of her movie business friends to agree to attend. “So-called friends found various ways of turning me down,” she says. “Everyone was scared back then, squeamish. I was angered by their in-the-closet attitude. But it’s not just Hollywood. The whole world’s so phony about AIDS, still. They act as if only homosexuals can get it. You should see the Senators’ faces when I tell them it can be transmitted vaginally. Unfortunately, AIDS is becoming a political issue, which worries me, but I’ll have to follow it where it takes me. I’ve always tried to do charitable things anonymously; but in the case of AIDS, I saw a chance to use my fame to do some good.”

That fame began back in 1944, when the release of National Velvet made Elizabeth Taylor a star at age twelve. In effect, she had stardom in lieu of a childhood.

“Let’s face it,” she says, “I was a freak. I didn’t see my first baseball game till last year. I never went to a senior prom. I don’t resent it now, but I did then. I wasn’t a normal teenager. I wasn’t doing the things my brother was doing or the girl across the street.”

This is said with no bitterness at all, but rather with a girlish wistfulness. Beneath her pronounced womanliness, there is something of the ingenue about Taylor, as if some part of her was frozen in the daydreamy movie world in which she grew up. It’s this obdurately girlish part of her that no doubt has contributed to her survival even as it probably has kept her from seeming fully mature as an actress—more often a coquettish flirt, a petulant adolescent, than a seasoned woman, like her anguished Martha in the 1966 movie version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a much lauded performance for which she won the Oscar. About this, too, she is candid, saying she never really thought of herself primarily as an actress.

“Only a couple of times has it been a stretch,” she says of her acting. “The truth is I was never very ambitious, never that concerned about getting this part or that, probably because of just plain laziness.”

And probably because of love, of which there was a lot, and alcohol and pills, particularly Percodan, of which there were a lot, all through the middle part of her life. Being stoned, she says, helped her get over her innate shyness, helped her escape.

“I am certainly a compulsive person,” she says, “though I really think I could have been even more so. But, usually before I reach the abyss, I start pulling back. All during my life I’ve been able to do that, to take the positive from the negative. It might sound very Pollyanna-ish, but I believe there’s a reason for everything, a lesson in it. The only time in my life I was bitter was after Mike’s death.”

Mike Todd, the flamboyant, street-tough producer of Around the World in 80 Days, was Taylor’s third husband and, by her account, first great love. They married in 1957 when she was twenty-four, he fifty. “It was fantastic,” she says. “I felt like I’d come home; no, I felt like I’d found home.”

That distinction between coming home, which means you know what home is, and finding home, which means you never had one to begin with, is typical of the care Taylor uses in talking to me about the men in her life. I find that she will, in fact, talk about them.

“I saw no reason for his death,” she says of Todd, who was killed in an airplane crash thirteen months after they’d been married, leaving her with their six-month-old daughter, Liza (Taylor had already had two sons, Michael Wilding, Jr., and Christopher Wilding, by her second husband). “For several years I couldn’t figure out why I wasn’t on that plane with him because I was supposed to have been. Then it became clear. If I’d been on that plane I would never have met Richard.”

Richard Burton, her fifth and sixth husband (they first married in 1964 and divorced a decade later, then married again in 1975 and divorced a year later), was, by her account, her second great, if tumultuous, love. In between Todd and Burton there was a five-year marriage to singer Eddie Fisher, of whom Taylor says: “Every time I married, I thought it would be forever, but I have no idea why I married Eddie. We talked about Mike all the time. Eddie had known him and idolized him, so it was a way of keeping Mike alive. I guess that’s pretty sick.”

Burton’s name, on the other hand, still brings tears, so much so that at one point, mid-reminiscence, she actually leaves the room. “I loved him for twenty-five years. We had a unique relationship. I was still madly in love with him the day he died and—he loved his wife—but I think he still loved me, too. I thought he’d always be there, at the other end of the phone. Even if we weren’t together, he was still in the world. When I realized I would never hear his voice again or see his face, his eyes…if I hadn’t been to Betty Ford before his death, I don’t think I’d be around.”

Starting in December, 1983, in a celebrated seven-week stay—as celebrated as anything she’d ever done—Taylor dried out at the Betty Ford Center for alcohol and drug rehabilitation in Rancho Mirage, California. What finally put her there, she says, were not the party-and-pain years with Burton, but her seventh and last marriage, to Virginia Senator John Warner.

“I just lost my identity,” she says. “We’d only been married three months when John decided to run. So we didn’t have the foundation of a relationship, the intimacy to fall back on. Then once he was in the Senate, I was redundant. The Senate is the most exclusive club in the world; it’s wife, mistress, lover, mother, family. I just ate and drank more. I think it was from pure loneliness. I usually face life straight on, but the perverse part of me said, ‘O.K., if you’re going to self-destruct, go to it. ’”

In an effort to get herself out of Washington and pull herself together, Taylor came up with what she smilingly calls “an outrageous idea’’—a tour in the play The Little Foxes.

“My friends tried to stop me,” she says. “They kept saying, ‘You have no theater training; your voice will never reach the back row.’ But I dug in my heels.”

During her twelve months on the road with the play, for which she drew some nice reviews, she says she talked to her husband more than when she was home. But that marriage to Senator Warner ended in divorce; and a year later she checked into the Betty Ford Clinic, exhausted, overweight, and addicted.

“I never felt so alone in my life,” she says of her stay there. “Actually, it was the first time I had really been alone, without a husband, a child, a secretary, somebody; the first time I slept in a dormitory with another woman. It was like being in a sorority. I had to ask some of the other women who’d been to college if that was what it was like. We all belong to the same sorority of addicts; Betty Ford is our alma mater.”

In the years since she graduated from the center, Taylor has not attended A.A. meetings, but has remained sober with the help of what she calls her own support group, which includes her equally copper-toned escort of late, actor George Hamilton, her four children (the fourth is a daughter, Maria, whom she and Burton adopted), and her six grandchildren. Her only dark times now, she says, are when she’s in pain—usually from an old back injury. She uses medication only when hospitalized, and has one vice left: cigarettes.

Taylor says she has no regrets and does not dwell on the past except when prodded by a persistent interviewer. As befitting an American icon, she has a kind of determined a historicism, an insistence on living in the present—which is both the strength and weakness of our so-called national character.

“In all the years, I never have explained my behavior or what the press has interpreted as my behavior,” she says. “They see my life as a yo-yo: good and bad, in and out, up and down. Right now, things are good; I seem to be on a roll. I’m sure I’ll fuck it up again,” she adds with a gusty laugh. “But I’ll tell you one thing: before I get married again, the bastard’s going to get a lot of scrutiny.”