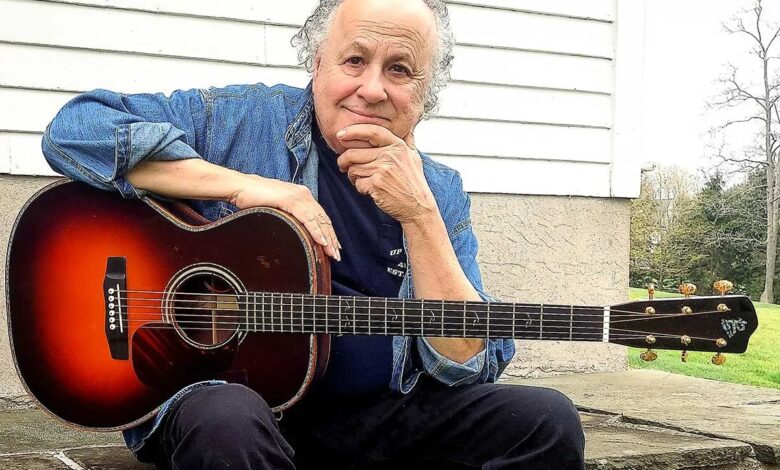

Guitar Talk: Arlen Roth Reflects on a Lifetime of Making and Teaching Music

Arlen Roth defies categorization. Over five decades, he’s played and/or toured with an astonishing range of artists: Ry Cooder, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Vince Gill, the Bee Gees, Huey Lewis and the News, Paul Butterfield, John Sebastian, Rory Block—the list goes on.

But Roth is more than a first-call sideman. He’s one of the most influential modern guitar instructors, first through Guitar Player magazine, then via books, tapes, and videos marketed through his own Hot Licks company, featuring rock, folk, jazz, blues, and classical greats. He even gave daily video lessons on Gibson’s website for five years. And private lessons, of course. Busy guy.

Since 1978, Roth has released 20 mostly instrumental albums on his Aquinnah label, showcasing his virtuosity in fingerpicking, strumming, and slide. Though best known as an electric guitarist—he even wrote Masters of the Telecaster—his love for acoustic guitar runs deep.

His latest Aquinnah release, Playing Out the String, is an acoustic collection of folk and blues nuggets (“Walk Right In,” “Diddy Wah Diddy”), Norman Blake tunes, Roy Orbison’s “Blue Bayou,” Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’,” and a moody instrumental take on “Pancho and Lefty.” He closes with his own bluesy title track.

Throughout, Roth showcases an impressive lineup of acoustic guitars—one, two, or three depending on the song—including a 1960 Stella 12-string, George Bowen custom OM, 1968 Martin D-28, 1957 Martin 00-17, 1934 Gibson L-00, 1930s National steel, and a Santa Cruz OM/AR (his signature model).

I caught up with Roth by phone from his home in southern Connecticut to discuss the new album, his approach to instrumental storytelling, his ever-evolving collection of instruments, and his pioneering work in guitar education.

When do you know it’s time to make an album? Are these songs you’ve had in mind for a while, or do they come together organically?

After a big electric album like Super Soul Session with [bass guitar legend] Jerry Jemmott, I like to follow up with a more introspective acoustic record. I’ve done five of these now, usually between what I’d call big projects—both in terms of the musicians involved and the budget.

The acoustic stuff is very personal for me. A lot of these songs were ones I’d wanted to record for years instead of just playing in the living room. Take “Walk Right In”—whenever I’d pick up a 12-string, that’s what I’d start playing, always with a little humor.

On the album, it’s surprising which songs get a vocal treatment and which are instrumental. “Pancho and Lefty,” for example—a story-driven song—works amazingly well as an instrumental.

That’s something I do a lot. I even did a full Bob Dylan acoustic instrumental album [How Does It Feel?].

I also did an acoustic Stones album [Paint It Black] and an acoustic Simon and Garfunkel record [Subway Walls and Tenement Halls]. Lyrics are secondary to me in terms of what I respond to. I take in a song as a whole—lyrics, sound, everything. If a song has a compelling guitar part at its core, that’s what usually draws me in.

So many Dylan songs have such beautiful and memorable melodies.

Exactly. I even talk in the liner notes of that Dylan album about how he doesn’t get credit for his melodies. I think he’s always been careful about making sure he had good melodic content, but I go even further and do songs like “Desolation Row.”

The beauty of lyrics is that you have to keep on creating something new every time it turns around, so I do that with the guitar, too. The last thing you want to do is make it sound like Muzak. You want to really sound like you’re singing through the instrument.

How do you “cast” an album, guitar-wise?

It’s not only the guitar that I like using, but it’s also what ends up recording the best on that day. I might come in with a ’30s Gibson L-00, but it takes time to pair it with the right mic and listen to it play back. It may work to me just sitting down with my guitar, but as soon as I’m in the studio, I might end up using a relatively new Santa Cruz guitar.

How many guitars do you typically have in the studio?

For this album, I had six or seven acoustics. I recorded with Alex Salzman, a wonderful engineer I’ve worked with for years at his studio, Salz Media. I feel completely at home there—he puts as much thought into recording as I do into playing, and he loves working with fine vintage mics.

I always have a 12-string, an old Stella, and a National steel on hand, but it really comes down to what fits the song. If I’m layering two guitars, I make sure they’re distinct—one might be more woody and the other more stringy. I love finding those combinations.

How many guitars do you own?

I have about 15 really good acoustics and a lot of electrics. The collection tends to shrink when you need money or realize, “I haven’t touched this guitar in five years.”

I have a couple of beautiful Santa Cruz instruments, including the Arlen Roth OM/AR model in both mahogany and rosewood. I love my Martins, too—one standout is a mid-’50s all-mahogany 00-17 that sounds fantastic. I also have a wonderful custom OM made by the late George Bowen in California, which he delivered to me in Connecticut.

Recently, I found an unbelievable 1954 Guild F-40 sunburst acoustic. It’s not on this record since I finished the album before I got it, but it’s definitely going to have a lot to say on the next one.

When arranging a song, your influences can come from many versions. “Diddy Wah Diddy” made me think of Ry Cooder, while “Randall Collins” and “Blue Bayou” have been covered widely. What shapes your approach to these songs?

Just the fact that the song touches me, and there are songs that have really stayed with me. I was trying to look for some other stuff as well, and that’s when I came across [Norman Blake’s] “Randall Collins.”

[With Blake’s “Church Street Blues”] I knew I wouldn’t match Tony Rice’s hardcore bluegrass approach, but I heard something that blurred the line between bluegrass and blues. Blake has a gift for writing timeless songs, and I wanted to tip my hat to him.I also love the Brownie McGhee song “Gonna Move Across the River.” To me, it all weaves into an American roots guitar tapestry. My goal is just to get these songs across to people—to say, “I love this for a reason, and I hope you hear it in my interpretation.”

Early in your career, did you ever dive deep into studying artists like Mississippi John Hurt or Blind Blake, or focus intensely on a specific genre?

Only in dribs and drabs. I’d take in the whole genre and then get snapshots of an artist like Son House, Robert Johnson, or Blind Blake—but never to the point of obsession. I like to jump around and pull influences from everywhere. For example, one time I spent a weekend in Toronto with John Prine and Leon Redbone…

Now there’s a duo I’d like to hang out with!

Yeah, for sure! Oh, and Jack Elliott was there too. I mentioned to Leon, “Y’know, Ry Cooder recorded ‘Diddy Wah Diddy,’”since I loved his version as well. He just said,“Oh, really?”—never breaking character. Like, “Oh, that guy did it too?”Meanwhile, he’s casually pulling bottles of wine from his attaché case, just being fully Leon Redbone.

He had that incredible ability to evoke something from 70 years ago. Both he and Prine did “Diddy Wah Diddy” so well that I wondered, is this overplayed? Should I really do this song? But then I thought, what the hell? Maybe I’ll introduce it to some people who haven’t heard it before.

What was your first acoustic guitar?

I started out on some pretty bad instruments I picked up from record shops. But when I was studying a bit of classical guitar in New York City, my teacher recommended a wonderful nylon-string Favilla. I still remember the smell when I opened the case. I only had it for a few months, though—my teacher kicked me out when I got an electric guitar.

Heresy!

Apparently. It was a four-pickup Ideal guitar from Japan. I was 11, it was 1964, and my dad and I bought it at Den’s Music, a little shop on 48th Street [in New York City]. And Charlie Watts was there! He gave me an autograph and signed it,“Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones.” They were playing their first New York show that night at the Academy of Music.

When touring with so many great musicians, did you primarily play electric, acoustic, or a mix of both in a given show?

It really varied. With Simon and Garfunkel, I must have had seven guitars onstage, switching between acoustic and electric. I even had one guitar with picks stuffed into the strings to create a kalimba or steel-drum effect, which I used on “Cecilia.”

With someone like John Prine, I played lead guitar and pedal steel. He’d start with an acoustic set before we moved into the electric set. With folk artists like Eric Andersen or Tony Bird—an incredible Malawian singer I loved playing with—it was all acoustic. One of my main guitars for those gigs was a beautiful 1939 000-18 I bought from Ry Cooder. Best guitar I ever owned. Every time I get another guitar, I’m chasing that sound.

Do you still have it?

No, I sold it. It was already falling apart—the top needed to be replaced—but I played it for 30 years. Even when I did the Rolling Thunder Revuemovie with Dylan, he borrowed that 000 from me. I remember he put a big belt-buckle gash in the back, which I was always proud of—“Look, Bob Dylan did this.” [Laughs] Before playing it, he asked, “No strap?” I said, “Sorry, no strap, Bob.” Joan Baez warned me, “You’re going to regret lending it to him without one.” But I said, “Come on, let him use it. It’s beautiful.” And he loved that guitar.

What are your thoughts on today’s guitar pedagogy? With so much available, is online learning now the norm?

With Hot Licks, I showcased real personalities—players who had spent decades honing their craft before ever making a video. Some were legends, while others, like Scotty Anderson and a young Eric Johnson, deserved more recognition. I wanted to give them that exposure.

Most instruction today feels rote—just “play these notes” without depth. I worked with real legends—Junior Wells, Lonnie Mack—letting the music speak. You don’t remember licks; you remember your teacher. That’s what Hot Licks was about—self-taught musicians passing on their experience.

Teaching also forced me to analyze my own playing. Someone would ask, “What was that thing you did?” and I’d realize, “Oh, I’m pushing the B string with two extra fingers.” I was figuring it out as I taught it.

I started with audio tapes, working with Happy Traum at Homespun, who got me my first book deal with Oak Publications for my slide guitar book—still widely read today. By 1984, just as I started to work on [the soundtrack for the movie]Crossroads, we moved into video. I kept doing both—if Tal Farlow did a video, he also did two audio tapes. Same with Steve Morse. I wanted to cover all angles.

What’s the latest thing you’ve learned, or the most recent artist who caught your ear and made you want to explore their work?

It’s not about one person—I just follow what inspires me. Late at night, I’ll sit down and think, why not try an acoustic instrumental of this? Lately, I’ve been drawn to Depression-era music like “Up a Lazy River” and “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”—songs that spoke to hard times and individuality, much like today. I also love Tampa Red, Blind Blake—who’s in a class of his own—and I’m diving into Blind Lemon Jefferson’s diverse catalog. His playing was so personal, and I ask myself, “How can I bring that forward without sounding like a throwback?” It’s always a balance.

You don’t want to just copy them.

No, but at the same time, I just love doing that. That’s the challenge.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.