How Trump Won the First “Influencer Election”

Moments after Donald Trump was declared the winner of the 2024 election, Dana White, the Ultimate Fighting Championship CEO, took the stage to thank those who helped deliver him the victory.

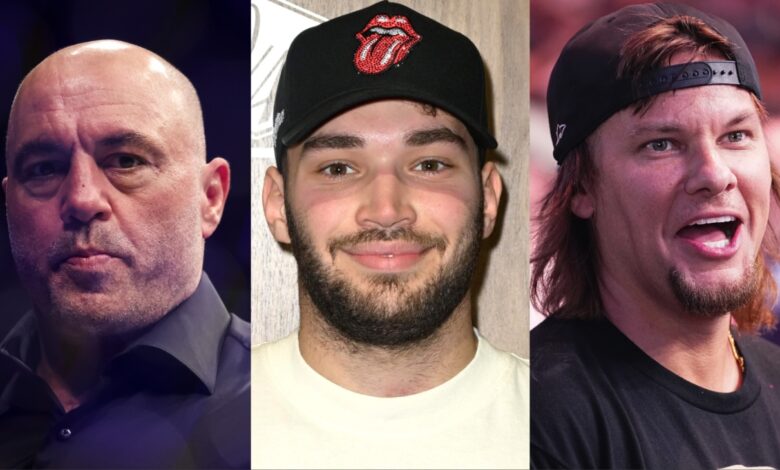

“I want to thank the Nelk Boys, Adin Ross, Theo Von, Bussin’ With The Boys and last but not least, the mighty and powerful Joe Rogan,” White said.

While half the country is reeling from the potential consequences of another Trump term, concerned about deepening social divisions, the dismantling of democratic norms and the normalization of far right extremism, there is one group that has emerged from this election cycle as a definitive winner: influencers.

The slew of influencers White acknowledged on stage are part of a sprawling network of online content creators that the Trump campaign centered in its media strategy, ultimately granting him unprecedented reach to win over voters and delivering him the election. “People have coined this the influencer election, and I think it’s the first of many influencer elections to come,” said CJ Pearson, national chairman of the Republican National Committee’s Youth Advisory Council, who helped the Trump campaign liaise with Gen Z influencers.

For the past two decades, the media landscape has been transforming. By nearly every metric, legacy media is in decline: average monthly unique visitors to websites for the country’s top 50 newspapers declined 20 percent to under 9 million in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to Comscore data, and the amount of time people are spending consuming legacy media content is getting shorter. The content creator industry, meanwhile, is ascendent. The influencer economy is set to surpass half a trillion dollars by 2027, according to a recent Goldman Sachs report, and 30 percent of consumers trust content creators more than they did six months ago, according to a 2023 report by Sprout Social, an analytics firm.

Throughout the election, both the Democrats and Republicans were forced to grapple with a radically transformed online news and media environment. Both parties courted creators by inviting them to their respective conventions, seating influencers front and center during rallies, funneling money to creators through political action committees and attempting to build up their respective candidates’ own followings across social media.

“This is the first election where the media landscape has really shifted,” said Loren Piretra, chief marketing officer of Fanfix, a creator monetization platform.

Influencers played a key role in manufacturing viral moments for each of the candidates. TikTok duo Carl Dixon, known as Casa Di, and his friend Steve Terrell, produced remixes of quotes from Trump’s running mate J.D. Vance that reached tens of millions across the platform, and content creators like @citiesbydiana helped mainstream the “Brat summer” trend through a steady slew of memes. YouTube stars the Nelk Boys and podcaster and comedian Theo Von hosted Trump and Vance on their respective shows, amassing hundreds of millions of collective views across platforms.

But while both campaigns worked overtime to court influencers, their strategies were divergent. The Harris campaign prioritized shortform clips, investing in quick videos and viral remixes on TikTok and Instagram. The Trump campaign went deep and long, investing heavily in longform YouTube podcasts and building partnerships with livestreamers. Ultimately, the latter proved wildly more successful.

The Trump campaign traveled to meet with various content creators, while Harris sought to make influencers meet on her own turf. When she and Walz filmed an episode of creator Kareem Rahma’s hit series Subway Takes, for instance, which is meant to be shot on a New York City subway, the Harris campaign insisted on filming it on a bus in Pittsburgh. When Harris was invited on Joe Rogan’s podcast, the campaign responded by requesting that Rogan leave his studio in Austin, Texas and travel to them. They also wanted to cut the format to an hourlong interview, rather than his notoriously long discussions that usually last three to four hours. The interview did not happen. The Harris campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

“Harris approached the creators as media channels rather than as collaborators, which is the biggest misstep marketers make when working with influencers,” said Brendan Gahan, CEO of Creator Authority, an influencer marketing agency, who has done work with democratic politicians. “Trump immersed himself in creator culture, met them where they were and embraced their mediums.”

Trump’s focus on building parasocial relationships also proved critical. “Impressions are not created equal,” said Gahan. “The bonds creators have with their audiences is what drives meaningful engagement and shortform creators just can’t achieve those bonds to the same degree. Harris did not do [many] longform engagements or outreach.” Trump going on podcasts like YouTuber Logan Paul’s Impaulsive or Theo Von’s This Past Weekend, however, gave fans of those podcasts the opportunity to parasocially bond with the candidate.

Trump also created custom experiences for creators, building tight personal relationships with them. For instance, he didn’t just invite the Nelk Boys to his rallies, he invited them on his private plane and FaceTimed their friends together.

Xavier Derusso, a conservative content creator based in Los Angeles, said that Trump’s work courting creators like TikTok star Bryce Hall or YouTube star turned OnlyFans creator Corinna Kopf, both of whom are deeply embedded in youth online pop culture, helped normalize supporting Republicans among the A-list Los Angeles influencer world.

Derusso said that creators used to worry about losing brand deals for supporting Trump, but things changed this cycle. “I used to get all these dirty looks and disbelief when wearing a MAGA hat. Suddenly, it’s people coming up to me with respect.’”

Jessica Reed Kraus, a conservative influencer who writes the Substack newsletter House Inhabit and has over 1.3 million followers on Instagram, said that Trump’s content influencer-packed election night party at Mar-a-Lago, which she attended, reflected the campaign’s commitment to the new media environment. “It’s a huge victory for us,” she said, “for those [online] who helped make it happen, and who got his message out. There’s a whole power shift. It’s just a testament to how much people have lost trust in the traditional media.”

But while the internet has democratized content creation, this new influencer-driven media climate comes with significant downsides. Because they view themselves primarily as entertainers, many content creators fail to adhere to traditional journalistic ethics or don’t disclose partnerships that present a conflict of interest. Influencers can also face pressure from the social media platforms they operate on to sensationalize content in order to perform well in algorithmically driven feeds.

Federal regulators have also failed to adapt to the new media world. During this year’s election cycle, campaigns and political action committees poured millions of dollars into social media agencies that partner with creators but received almost no regulatory oversight. The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, a nonprofit legal and public policy institute, urged the FEC to update its rules to ensure more transparency around how candidates pay influencers last year. “Voters deserve to know who is seeking to influence them,” the Brennan Center wrote in their letter to the FEC.

Though the Democrats ultimately lost the election, many liberal creators ultimately gained a larger audience by covering the campaign and are walking away from this cycle with a significantly larger platform than when they started.

Keith Edwards, a Democratic strategist, launched a YouTube channel in May and gained over 207,000 subscribers by posting nonstop election videos, interviewing figures like democratic advisor Anita Dunn and Pete Buttigieg, going live during Trump’s assassination attempt and attending the DNC as a credentialed creator. Elizabeth Booker Houston, a political content creator and comedian, gained over 100,000 Instagram followers which led to her first comedy tour. Harry Sisson, a 22-year-old TikTok star known for pro-Democrat commentary, nearly doubled his audience as the election season unfolded. “I think [the election] was kind of a perfect storm that allowed folks like myself and other creators to grow our platform,” he said.

Experts on both sides of the aisle said that this election was a watershed moment for independent media. The shift towards a more digital and personality-driven news and information landscape will likely only accelerate under a Trump presidency, as his administration continues to shun traditional media. Throughout his first term, Trump leveraged online influencers to erode trust in democratic institutions, evade accountability and spread dangerous politically-driven misinformation.

Jess Rauchberg, assistant professor of communication technologies at Seton Hall University, said that regardless, political campaigns will be forced to adapt to this new environment and will “be chasing the podcasters and the independent news creators.”

“Legacy media is dying,” said Rauchberg. “I don’t think it’s dead yet, but it’s going to accelerate pretty quickly, and people are going to turn to alternative news sources, they’re losing trust in traditional news. I’m seeing that across the political spectrum. It’s not just conservatives or progressives or liberals or centrists or independents. It’s everyone.”