“I gave my vintage Jazzmaster to a girl after a show in Liverpool. 30 years later she sent me back the guitar. It’s like it died and went to heaven and came back to me”: The miraculous return of US shoegaze pioneers Drop Nineteens

“I gave my vintage Jazzmaster to a girl after a show in Liverpool. 30 years later she sent me back the guitar. It’s like it died and went to heaven and came back to me”: The miraculous return of US shoegaze pioneers Drop Nineteens

Almost every successful band has a similar story. They form, play some covers, write some originals and play loads and loads of shows, gradually climbing their way up the fickle rock ’n’ roll totem pole until they get noticed and signed. Then, there are the rare exceptions – like Boston shoegaze quintet Drop Nineteens.

When they formed in 1990, the home-recording band had no industry connections, prior recording credits or experience playing live. Yet almost before they could fumble their way through a full set, Drop Nineteens were shuttled to England, embraced by the British media, put on tour with UK groups and signed to a subsidiary of Virgin.

“We went straight from being these totally unknown college students to being considered this big thing,” says frontman/guitarist Greg Ackell.

“It was insane. We didn’t have a record deal or anything one minute, and before we know it, the Cranberries and Radiohead are opening for us.”

The origins of Drop Nineteens are almost as remarkable as their highly unexpected comeback after more than 30 years. They formed in 1990 in a dorm room at Boston University, which most of the members attended.

Soon after they met, Ackell, co-vocalist Paula Kelley, lead guitarist Motohiro “Moto” Yasue, bassist Steve Zimmerman and drummer Chris Roof recorded a demo heavily inspired by the gauzy, ethereal soundwashes of UK shoegazers My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive.

While the shoegaze scene was thriving in the UK at the time, it was under-appreciated in the US, where aggressive alt-rock and grunge were moving the masses. So, Drop Nineteens – who couldn’t get a gig in their home town – sent their demo to English magazine Melody Maker and were rewarded with “Single of the Week” accolades before ever stepping onstage.

Word spread and demand for the demo was strong. Soon, the showers of praise turned into a waterfall, and UK labels looking for the next wunderkinder of shoegazing, came calling.

Drop Nineteens were invited to play shows in England opening for Chapterhouse, and before they could learn the difference between an escalator and a lift, the band was signed to Virgin-owned Hut Records (home of the Verve and Moose) in the UK, and Caroline (Smashing Pumpkins, Monster Magnet) in the US.

As thrilled as they were with the record deal, Drop Nineteens didn’t want to be lost in an ocean of pedal pushers, so they downplayed the heavy effects that swarmed through their demo, and wrote an entirely new set of songs for their debut album, Delaware, which they tracked at Downtown Recorders Studios in the Cyclorama Building in Boston, where Pixies recorded Doolittle.

While Delaware was hazy and multi-hued, it was also visceral, containing an externalized angst that hung heavy in the songs and hinted at an underlying tension within the melancholy.

“I liked a lot of the bands that were influenced by My Bloody Valentine, but I think we equated ourselves with the Pixies and Sonic Youth slightly more than we did with My Bloody Valentine and Cocteau Twins,” Ackell says.

“So, even though it’s a similar genre, Drop Nineteens were one of the few American outliers in that scene, and that’s maybe why we stood out from a lot of those other bands.”

“I wonder if there would even be a modern American shoegaze scene without the flag Drop Nineteens planted nearly 30 years ago,” says Internet radio station DKFM founder and president, DJ Heretic.

“They brought a sense of menace and an immediacy that made an impact. [Without them, that kind of music] just wouldn’t have been as relatable to a younger generation of American music fans.”

I wonder if there would even be a modern American shoegaze scene without the flag Drop Nineteens planted nearly 30 years ago

DJ Heretic

When the shoegazer scene was at its peak in the UK – just prior to the arrival of Drop Nineteens – only a handful of US bands, including Bethany Curve, Lilys, Velocity Girl, Swirlies and Medicine, rooted their indie rock sounds in the technicolor pool of shoegaze.

These groups all enjoyed multi-album careers and loyal fanbases, but it was arguably Drop Nineteens that had the most lasting impact on future generations of artists and fans weary of the macho posturing of grunge, the attitude-laden irony of US indie rock, and the pretense and affectations of some English shoegazer music.

From the start, Drop Nineteens were driven to be authentic and credible. The demo songs that got Drop Nineteens signed swam through rivers of reverb, delay and chorus and bore comparison to their favorite UK bands.

With Delaware, however, they discarded much of the ethereal window dressing, while retaining the tones and aesthetics of their demo. The album was praised for its diversity, strong songs and the band’s frequent shifts between volatility and vulnerability.

“From the swirling guitars to the fey vocals, and songs about longing for lost love, the British scene had all the expected trademarks and signposts of a rich UK musical tradition,” DJ Heretic says.

“With Drop Nineteens, there was no climbing through textures and colors to get to the sonic sparkle at the center of a song. Drop Nineteens sounded like disaffected college-town youth cutting to the heart of the matter. And that’s not something you can fake to an audience that demands authenticity above all else.”

Drop Nineteens kick-started their US success with the simultaneously dissonant and gorgeous guitar tangles of Winona, which earned airplay on MTV. They followed with the instrumental fan favorite Kick the Tragedy, and then dropped a blinding cover of Madonna’s Angel.

For their efforts, the band earned an opening slot on the US Chapterhouse tour and returned to England where they opened for My Bloody Valentine and recorded a radio session with legendary BBC DJ John Peel. But the avid praise was accompanied by overwhelming pressure.

Ackell and his bandmates were ambivalent about being viewed as part of a vibrant English scene and they were uncomfortable touring Europe before they felt road ready. The internal friction that resulted from the turmoil caused the already volatile band to slowly self-destruct.

Drop Nineteens’ second album, National Coma – which followed the departure of vocalist and co-guitarist Paula Kelley and drummer Chris Roof – was an intentional brush off to the entire shoegaze scene, and shortly after it came out in 1993 Ackell broke up the band.

Too thin-skinned to skillfully navigate the prickly, turbulent record business, he stopped listening to music, largely avoided his bandmates, and for decades remained oblivious to the cult-like status Drop Nineteens achieved among generations of American shoegazers and their fans.

I discovered that pursuing a career in music didn’t appeal to me because once that dream came true, the actual life didn’t make me happy

Greg Ackell

“I was turned off to the whole thing and I decided to see what else I could do with my life,” Ackell says. “I mean, when I started out, I loved music and being in a band, and I made the dream happen.

“But then I discovered that pursuing a career in music didn’t appeal to me because once that dream came true, the actual life didn’t make me happy. I’m pretty insecure, and I couldn’t handle it, so I stopped and didn’t look back for a long time.”

Ironically, while Ackell had his back firmly turned on music, Delaware became a cult favorite in the emerging US shoegaze scene, a scene that long outlasted the British movement, which was treated with derision after the arrival of Britpop.

For more than two decades now, Drop Nineteens have been cited as a major influence on a new breed of shoegazers, including members of Wishy, Horse Jumper of Love, Computerwife, Cryogeyser, Deerhunter, Warpaint and a host of other bands.

In late 2021, almost on a whim, Ackell decided to start writing songs again, all of which led to the reunion of Drop Nineteens and the release of their breathtaking new album, Hard Light. More mature than Delaware, the album substitutes reflection for rage and is rife with evocative, ruminative songs that echo and chime, but remain grounded.

Sonically, it’s a record that could have followed Delaware, matching buzzing, layered guitars with clean, iridescent strumming, and including warbly mid-sections and soaring reverb-laden passages.

“We never followed up Delaware with something that was written with that same mindframe,” Ackell says. “In that respect, the new album is very much a follow-up to Delaware. It is not Delaware 2, but in a way it’s like a long-missing album that we never made.”

Comeback albums rarely live up to their long-ago predecessors, largely because the musicians involved have moved on. That’s not the case with Hard Light. Having been absent from music for so long, Ackell imbues his new songs with youthful wonder and joy, and his reunion with his old bandmates is a time warp to a more innocent time, yet one somehow burdened by the pains of age and experience.

Drop Nineteens flared like a shooting star for a brief time and disappeared. Now, against all odds, they’ve returned with an album that can be cherished by old-school fans of Slowdive and Ride, as well as younger listeners, who prefer Hotline TNT, Nothing and Feeble Little Horse – bands about which Ackell remains blissfully oblivious.

I’m getting asked about every fucking shoegaze band on earth right now, and I just don’t know any of them

Greg Ackell

“I’m getting asked about every fucking shoegaze band on earth right now, and I just don’t know any of them,” Ackell says.

“I’m learning about them and I’m open to hearing everything. I’m proud that something I did inspired other people in bands, but I feel like I need to do more homework and more studying before I can really talk about any of them.”

In one of his first in-depth interviews since the release of Hard Light, Ackell offers his take on the English shoegaze scene and sound, discusses how and why Drop Nineteens recorded Delaware without reverbs or delays, and provides insight on why the band’s second album, National Coma, was so different than its predecessor.

He also addresses why he abandoned music for 30 years, what he did during his time away, what brought him back to the band he founded, the recording process for Hard Light, and how his life has changed between the time he was an arrogant, unstable rock star rubbing elbows with Kevin Shields and his reunion with bandmates he hadn’t seen in three decades.

How did you discover shoegaze music?

There’s something about the promise of a chord that’s coming but doesn’t quite come that creates tension and, in a way, it’s romantic in a literal sense – something promised but not delivered

Greg Ackell

“I always liked atmospheric bands, dating all the way back to the Velvet Underground. But then you fast forward to the Eighties in that same space, and there was something about the psychedelic sounds and repetitive phrasing of Spacemen 3, and the guitar noise of the Jesus & Mary Chain that really appealed to me. But it was Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation and My Bloody Valentine’s Isn’t Anything that really got me into guitars.”

My Bloody Valentine frontman Kevin Shields is widely credited as the most significant pioneer of shoegaze. The way he blended distorted guitar with backwards digital delay and heavy reverb created mesmerizing tones. And the way he held the tremolo bar and wobbled it as he played became a trademark technique of the genre.

“There’s something very disconcerting about that sound. Kevin once told me that what happens is that the chords are always detuning and the listener is always trying to hear the chord in the correct register, which is being alluded to, but by using the tremolo, it’s never really delivered.

“There’s something about the promise of a chord that’s coming but doesn’t quite come that creates tension and, in a way, it’s romantic in a literal sense – something promised but not delivered.”

Sonic Youth were influential to alternative and indie rock, and the way they used alternate tunings and dissonance was groundbreaking. How did they factor into what you did with Drop Nineteens?

“Their album Daydream Nation came out in 1988 at around the same time as Isn’t Anything and it was so jarring and interesting. It didn’t sound like anything else out there. They were an incredible band that made their own rules, which I really admire.”

The demo that earned you accolades in the UK was loaded with reverb and delay and seemed influenced by Slowdive.

“We were making it up as we went along. We weren’t a band that played in clubs. We just recorded songs in our dorm room influenced by stuff we liked. We made a demo, and we didn’t know what to do with it, so we sent it to Melody Maker without a record deal or anything.

“We had no real goals, and we didn’t expect anything. We were 18- and 19-year-old kids and we were all in school and trying to do well there and make this music at the same time, and suddenly everything blows up. It was crazy and totally unplanned.

“At the time, my thinking was, ‘Oh my God. If I could only get a record deal, make just one record, and play on a stage, that would be incredible!’”

You used some effects on Delaware, but you didn’t pile on the guitar pedals, which is something that differentiated you from some of your British influences. It was shoegaze and featured many of the elements of bands like My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive, but there was a distinct focus on songs, not just sounds.

When we went in to do Delaware, we completely abandoned pedals. You can do amazing things with pedals, but in my 19-year-old mind, I went, ‘Hey, pedals aren’t cool anymore. They’re lame’

“When you listen to Spacemen 3, there are trippy sounds there, but they’re very natural. You can’t hear choruses, flangers, and distorted wah-wah all over the place.

“So many bands loaded up their pedalboards and went crazy with stacked effects and overly produced records. Cocteau Twins were a big influence on a lot of those bands, and [frontman] Robin Guthrie co-produced the first Chapterhouse album.

“It became all about these sounds. It was a bit too much for my ears. So, when we went in to do Delaware, we completely abandoned pedals. You can do amazing things with pedals, but in my 19-year-old mind, I went, ‘Hey, pedals aren’t cool anymore. They’re lame.’ There was a wah-wah on our cover of Madonna’s Angel, but all the other sounds were achieved by setting up amps in different ways.”

How did you achieve ethereal guitar textures and echoes without reverbs and delays?

“We experimented. We put two Vox AC30s facing one another in a room with high tremolo on. So, that’s an effect, but the effect is in the amp, not a pedal, which to us seemed more authentic. And we had a Marshall stack in the main room blasting to the high heavens. Then, in the isolation booths, we had the shittiest little Peavey amp set at a tone that cut through.

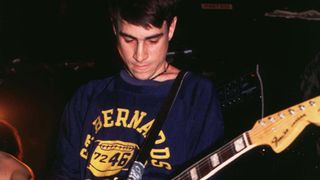

“And me and Moto played all these Fender Jaguars and Jazzmasters in the control room, then stacked them. We mixed everything to taste, depending on what song we were doing. I don’t think any song has just one guitar amp sound. Everything was a blend, and that’s how we made all the different guitar sounds.

“We created the delay sounds naturally by having amps in one room and mics further back and in different places. It was the same thing David Bowie did when he sang Heroes, and when you do that you get that cool plating effect.”

How did you replicate your tones when Drop Nineteens toured for Delaware?

“We knew we had to reinvent what we did in the studio, but we didn’t even try to approximate the sounds on the album. We just wanted to be loud when we played. So we turned everything up. I really wonder if we were trying to make up for a lack of musicianship by creating this assault on everyone’s ears.”

Was it frustrating to be lumped into a the UK scene when you weren’t British and strived for a different sound?

“It’s true that I was annoyed by that, so I rebelled. I was young and arrogant, and I came away from that whole touring experience saying, ‘Yeah, well they like us, but for all the wrong reasons. So, I’ll show them.’

“It was pretty silly, and not very gracious. But that’s one of the reasons our second album, National Coma, was such a sharp left turn. That record is the sound of me searching for something and screaming most of the time. It’s a weird record and I don’t like it that much.”

National Coma was more American sounding, but there was a lack of the strong hooks and choruses that made Delaware so enjoyable.

“I just think that if you’re honest with yourself, you can decide you want to sound like something, but invariably you’re going to sound like yourself. On that record I didn’t want to sound like anything and that’s what it sounds like. In a way, it was me trying to do something that no one would expect from us. I wanted to surprise people. And I don’t think too many people were happily surprised.”

Was it the reaction to National Coma that caused you to quit the music business?

“It wasn’t the death knell. I knew I wanted to leave the band and stop doing music before that, but I didn’t want National Coma to be the last thing I did. I recorded one more album under the name Fidel. I funded it myself and was offered a deal, but I decided not to release it because I couldn’t stand the idea of being back under the microscope.”

Music was no longer my dream, it was my job, and it didn’t make me happy

Greg Ackell

Why did you leave the music business for so long?

“I was very unhappy, and it was music that was making me unhappy. I hated music and stopped listening to it. I was no longer a fan. And that was crazy because it had been so important to me before then.

“Growing up, I didn’t think I’d ever be able to do music for a living or be successful at it. I wanted to. I dreamed of doing it, but I didn’t plan on it and those are two very different things. So when my dream came true, the bubble burst.

“Music was no longer my dream, it was my job, and it didn’t make me happy. I was very controlling, and I was not kind. And I think some of that intensity I directed towards people came from my unhappiness.

“So I decided to go be with my girlfriend and discover what I was going to do next in my life. I had no idea that there were all these bands that were starting to love Delaware or that bands would form over the years and be influenced by what I did. I’m flattered now, but that was totally off my radar.”

After a 30-year absence from even listening to music, what inspired you to write and play again?

“In the very early aughts, I heard this band the Clientele [whose song Policeman Getting Lost we covered on Hard Light]. And listening to them really brought me back and made me want to hear other new music. I discovered Spoon, who brought me back in a much more serious way and I became a serious fan of music again.

“It was exciting to be back in a place I thought I’d never get to, and I started listening to LCD Soundsystem and this band I love called Car Seat Headrest. Those are the kind of bands that move me now.”

I discovered Spoon, who brought me back in a much more serious way and I became a serious fan of music again

Greg Ackell

How did you go from rediscovering indie rock to reforming the band?

“[Bassist] Steve [Zimmerman] was the only one I had stayed in touch with over the years. One day I started wondering what a new Drop Nineteens song would sound like. But I didn’t have a guitar around. I told Steve what I was thinking and he went on Reverb.com and overnighted me a [Squier] J Mascis Jazzmaster.

“I was so pleased because I come from an era where we played Jazzmasters and Jaguars. And it wasn’t because these other shoegaze bands played them, it was because we couldn’t afford Telecasters and Stratocasters. Whereas you could get vintage Jaguars and Jazzmasters for five or six hundred bucks back then. They’re worth so much now.”

“Our guitarist Moto has a ’64 blue Jaguar and it’s worth about $20,000. But back then, we had lots of those things. I actually had a vintage Jazzmaster that I played in the Winona video, but I didn’t like it that much. I’d usually reach for another guitar on tour. I don’t know why, but I gave it to a girl after a show in Liverpool when we were on tour. Of course, she had no idea where I had been for 30 years.

“Then, I was on social media – which I never used to use – and she sees me on there and reaches out to us and says, ‘Hey Greg, I’m glad you’re alive. I’ve got your guitar.’ And she sent me back the guitar from Liverpool. It’s like it died and went to heaven and came back to me. And now I love it. It’s the only guitar I have left from the original Drop Nineteens.”

Your readers are going to throw up when they read this. I hadn’t played a guitar for 20-odd years

What happened after Steve sent you the guitar? Did you start playing and writing right away?

“Your readers are going to throw up when they read this. I hadn’t played a guitar for 20-odd years. I didn’t even pick one up – not once. I remembered how to play, but I didn’t have a tuner here or anything. So, I took the guitar out of the box and tuned it to itself. I didn’t bother tuning it to the low E. I tuned it to 440, but I was in the key of C minor when I started writing the new songs. And I never tuned it back.”

Wouldn’t the songs have sounded brighter and more ethereal if you used standard tuning?

“Here’s the thing – I didn’t write everything in C minor because I’m an idiot. I mean, I am an idiot, but what happened was I started to like the sound of my voice when I played the chords tuned down. The songs sounded a little weary, and the music seemed like I was searching. So that became part of the sound of Hard Light.

“It’s funny. Life affects your sound more than anything, and sometimes it’s just happenstance. It’s not so much a matter of what you are doing to the sound so much as what life is doing to you and how the sound is affecting you.”

Did the new songs come easily?

“When I picked up the guitar, I didn’t know if I could still play or could sing or write or had anything to say. And I didn’t know if I’d be able to put lyrics on anything I came up with. The crazy thing was that I had so much to express, so none of it was a struggle and none of it was hard to find. I wrote over half the songs over the course of the first weekend when I got the guitar. It took us 30 years to come back and, ostensibly, it took me just a few days to write most of the record.”

Once you realized you had the material, you called Steve and the two of you put Drop Nineteens back together. Then on January 18, 2022, you posted on Twitter that the band was back.

“I didn’t even know how to create a Twitter account. Steve created it and I posted this letter announcing our plans. And it got picked up by some of these different music news websites that morning. I don’t even know how they found it. But without that, I might not have seen this through. If people didn’t know I was doing it then I wouldn’t have to finish it. For a while, I was thinking it was a little premature for us to have said anything. But, in retrospect, I realize it was a smart move.”

Did you record Hard Light the same way you recorded Delaware?

“Working on it reminded me a little bit of how we did Delaware. Except this time, instead of being in a space with all these amps in all these different rooms and mixing the sounds together, we were on laptops, or an interface, switching through all the sounds, which is kind of the same thing we did back then but with modern technology.

“In a very practical way, we flipped through sounds and blended them. And I think the sounds we came up with are as good as anything we did on Delaware. We mic’d a Vox amp and some of the little crappy speakers we used. We bought the cheapest modeling amps you can buy on Amazon and I had those things behind me while we recorded. And I swear to God, some of the coolest, most powerful sounds came from those little things.”

Was Logic hard to learn?

“Well, yeah, and I still am not really that good at using it. Steve got pretty good with it, which is good. I’m in New York, Steve’s in Boston, our drummer Pete Koeplin is in Boston, Paula’s in L.A. and Moto is in San Francisco, so we knew that sharing files was going to be intrinsic to this project.

“Everyone has lives. There was no way we could all fuck off to Barbados like rock stars, do a bunch of drugs, and do the whole album there. So, Steve and I worked together and used everything under the sun that we had at our disposal.”

That we’re back is a miracle unto itself, especially to me

Greg Ackell

In the early Nineties, there was a lot of friction and conflict in the band, which added to the excitement of the music. Does that still exist?

“No, we’re all getting along spectacularly well. We’ve all grown up and are happy to be making new music together. That we’re back is a miracle unto itself, especially to me. I’m the last one anyone ever expected would come back and play in the group. But one of the greatest things in my life isn’t just making this record, it’s having these people back in my life again.”

- Hard Light is out now via Wharf Cat.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month**

Join now for unlimited access

US pricing $3.99 per month or $39.00 per year

UK pricing £2.99 per month or £29.00 per year

Europe pricing €3.49 per month or €34.00 per year

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Prices from £2.99/$3.99/€3.49