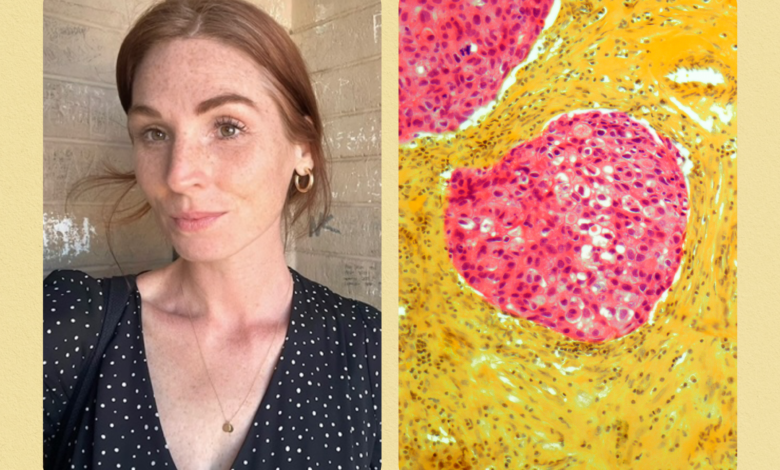

I Was Diagnosed With Breast Cancer at 36. Here’s How I Caught It Early

The story of my breast cancer diagnosis is full of unlikelihoods. For one, there was my age, 36, which made me an unlikely candidate for an illness that’s most common in people over 70. My generally good health, which was confirmed by annual blood tests with my GP, also suggested clear skies ahead. When I started experiencing my sole symptom, a subtle but persistent pain in my right breast, my doctors believed it was extremely unlikely to be cancer-related. It was far more probable, they said, that it was linked to hormonal changes from my menstrual cycle, or an injury I couldn’t remember.

A year and a half later, I know that unlikelihood doesn’t confer actual safety. People in their 30s get breast cancer. People in otherwise good health get breast cancer. People with rare or few symptoms can learn that those symptoms are, in fact, from breast cancer.

I was extremely fortunate that I saw doctors who were willing to follow up with testing, despite all of these unlikelihoods. After a mammogram, an ultrasound, two MRIs, and a biopsy, they found my stage I invasive ductal carcinoma while it was still mercifully small, and before it could spread to any nearby lymph nodes, which can circulate tumor cells.

When I look back, it’s easy to imagine how it all could have gone differently. I requested the initial mammogram and ultrasound because I felt certain that the pain—more of a concentrated burn than a cramp or ache—was unrelated to my menstrual cycle. When those tests came back clear, I took an even bigger leap and requested an MRI. I felt embarrassed—mortified, actually—at the thought of wasting an oncologist’s time and resources. Because I wanted to be a “good patient,” both logical and deferential, I came chillingly close to dropping my concerns. But, in a crucial decision, my breast surgeon agreed to order additional imaging based on my family history, which suggested I was at higher risk.

My first MRI turned up a “non-mass enhancement”—a lesion that doesn’t meet the criteria of a defined mass and can be either malignant or benign. Cancer still seemed unlikely, but that ambiguous scan was enough to get everyone’s attention. My doctor ordered a follow-up MRI for six months later, which located a small mass exactly where the pain had been.

In the time since my treatment, there’s been no shortage of “what ifs” to keep me up at night, but there’s one thought that feels especially searing: What if I hadn’t trusted my gut that the pain was dangerous? What if there hadn’t been any pain at all?

Research has shown that younger people with breast cancer are more likely to experience diagnostic delays. This can have devastating effects. According to the Cleveland Clinic, cases of breast cancer in young people are sometimes “more advanced when diagnosed” and “harder to treat,” having had time to grow and spread.

This makes intuitive sense: Absent any symptoms, I would have waited until I turned 40—possibly 45—before ever considering a mammogram. What I didn’t know until after my diagnosis is that I would have been behind schedule. I’ve since learned that the mammogram recommendations are more detailed than I realized—and that I’d missed a few potentially life-saving finer points.

Eric Winer, MD, the director of Yale Cancer Center and president and physician-in-chief of Smilow Cancer Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, tells SELF that there’s not quite a consensus on when cis women and people assigned female at birth should begin getting mammograms. Though the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended age to 40 in a new set of guidelines released in May of last year, “There has been a back and forth between 40 and 50” across health authorities, Dr. Winer explains.

“A number of years ago, the American Cancer Society (ACS) took a very measured approach and set the age at 45 for average-risk women,” Dr. Winer says. “Now, it says that women have the option of starting at 40, but should begin obtaining annual mammograms no later than 45 and continue that approach for at least the next decade. At age 55, they have the option of switching to an every-other-year schedule.” This continues for as long as the patient is in good health and is expected to live at least another 10 years.

The key words here are “average-risk.” High-risk individuals have their own set of screening rules. “We recommend that a woman with a family history of breast cancer, which could include their mother, sister, aunt, or grandmother, consider starting mammograms 10 years prior to the age at which that person was diagnosed, or starting at 40—whichever comes first,” Michelle Specht, MD, the codirector of Avon Comprehensive Breast Evaluation Center at Massachusetts General Hospital and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, tells SELF. “If a woman has a family member diagnosed with breast cancer at a very young age—under 40—then we use breast MRI to screen between the ages of 25 and 30,” she explains. “I worry that women are not aware of current screening guidelines.”

I wasn’t. Applying this rule to my own family history, I should have gotten annual mammograms starting at around age 34. Applying it to my family’s future, I’ll encourage my daughters to request MRIs beginning at age 26—10 years before my age at diagnosis—unless the recommendations change.

Dr. Specht notes that the majority of breast cancers discovered in women under 40, which represent 7% of all new cases, are found in people with genetic abnormalities or strong family histories of the illness. However, there are other risk factors that should trigger early screening, as the ACS advises. These include having had chest radiation before the age of 30, or living with health conditions including Li-Fraumeni syndrome and Cowden syndrome.

Having a lifetime breast cancer risk over 20%, as calculated by a Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BRCAT), also suggests you should begin screening early. Prior to my diagnosis, I had never undergone this type of risk assessment, but I’ve since learned that my own lifetime risk was 33%, well above the national average of 13% and above the threshold for early screening. The National Cancer Institute provides an online version of this tool, which you can try at home. By sharing your results with your doctor, you can begin an important conversation about your risk level and find out whether you’re a candidate for early screening.

Dr. Winer adds that there’s another insidious way that you might be vulnerable to breast cancer without realizing it. He says that factors like race, financial status, education level, and even relationship status can all affect your prognosis—especially if you’re young. “Being anything other than a middle-to-upper-class, partnered white woman puts you at higher risk. If you are a 20-year-old Black woman, you have twice the risk of dying from breast cancer compared to a 20-year-old white woman,” Dr. Winer says, noting that this gap is most likely explained by inequitable access to screening and treatment, not biological differences. “That’s a shocking statistic, and one that speaks to how much work we have to do as a country,” he adds.

But Dr. Winer also offers cause for hope. “We are really making a lot of progress in research, and treatment is very different today than it was even 10 years ago,” he explains. “Our treatments are better, and mortality is down. We still have over 40,000 women dying from breast cancer each year, but there are 300,000 cases annually. Most women with breast cancer become long-term survivors.”

“It’s hard to predict where it will be 10 years from now, but I think breast cancer is going to be one of the first cancers where we’re going to be able to say that we’ve virtually eliminated mortality,” Dr. Winer says.

For now, early detection is still one of the greatest tools we have in the fight against breast cancer. Everyone—but especially people at high medical risk and high risk of care disparities—should know the signs and symptoms, and be proactive and persistent in communicating any concerns they might have to their doctors.

I was lucky. Because my cancer was detected quickly, I was spared the most difficult forms of treatment. I was able to have a lumpectomy—a localized surgery to remove the tumor—rather than a mastectomy, which would have removed one or both of my breasts. I underwent radiation, but didn’t require chemotherapy as part of my treatment plan. I’ll continue to take a daily endocrine therapy medication for the next five to 10 years, but I have reason to believe the worst of this experience is behind me. My prognosis is, thankfully, very good.

While the majority of people under 40 don’t need to get annual screenings, it’s important to know if you do. I wish I had. Being aware of your risk level can improve your chances of a safer outcome in the unlikely event of an early diagnosis. Having gone through it myself, I know I’d do just about anything to improve those odds.

Related: