What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in ‘A Complete Unknown’

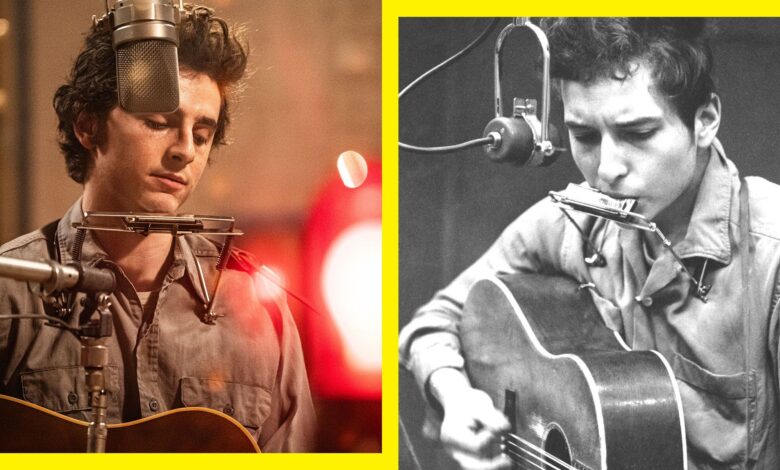

EVERY TRUE LIFE to silver screen adaptation plays fast and loose with the truth. Whether it’s the compression of characters into composites or just rearranging the narrative to make a better dramatic effect, stories shift all the time—and that’s certainly the case with A Complete Unknown. James Mangold’s return to the musician biopic tells the story of Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) in the early to mid-1960s. Trying to cut down that much of a person’s life into a movie-friendly runtime is bound to result in some changes to the actual record of events.

While there are a number of “inaccuracies” in Unknown, they range from minor to major (just chords, right?). While some of them are more important than others, there are a wide suite of changes to ensure a more dramatically effective tale. And it works—Chalamet’s electric performance elevates a standard biopic into something as memorable as the legendary singer himself. If you’ve seen the film and are looking to determine what’s fact versus fiction, here we highlight what we believe to be seven of the biggest differentiators.

Oh, and it goes without saying, but spoiler alert for the plot of A Complete Unknown and the life of Bob Dylan. Let’s get into it.

Dylan’s Angels

Bob Dylan does have several love interests, as shown throughout the movie, and each of them all have some details stretched or shifted accordingly. Let’s start with Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro). The first encounter between Baez and Dylan wasn’t a chance. Baez told Rolling Stone in 1983 that she went to Greenwich Village to hear Dylan play — alongside her then-boyfriend, who wasn’t super keen on Bob. Dylan and Baez also never spent a night together during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Additionally, she and Bob didn’t perform “Girl From the North Country” during the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival, but rather, “With God on Our Side.” Additionally, the on-stage battle over the setlist in 1965 never occurred, and the two never played together at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival (more on that later).

Elle Fanning’s Sylvie Russo is based on a real person, but at Dylan’s request, she changed her name. The real-life Suze Rotolo does, in fact, appear on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and the two did meet at a church folk concert. However, the real Suze left New York for six months, not twelve weeks. Also missing from the movie? The fact is that the real Suze got pregnant with Dylan’s child at some point in 1963 but ended up getting an abortion. The two officially broke up in 1964, as charted in Dylan’s “Ballad in Plain D.”

Finally, two quick notes: Laura Kariuki’s Becka doesn’t appear to be real and the film left out Carolyn Hester. Hester recruited Dylan to come to play harmonica on a recording of “I’ll Fly Away,” which marked Dylan’s first-ever studio session.

Shifting Recording Dates

A handful of Dylan’s songs see their original recording dates adjusted to better serve the narrative of the film. “Blowin’ in the Wind” could be heard in Village coffeehouse in the spring of 1962, not in October of that same year as the movie suggests. Additionally, “Like a Rolling Stone” was recorded before “Highway 61 Revisited.”

Dylan and Guthrie

Connecting with Woody Guthrie was Dylan’s major priority when he first arrived in New York, but he never met the singer in a hospital in the middle of the night. In real life, Dylan ventured out to meet his idol at his home in New Jersey after connecting with Guthrie’s children in Queens. Additionally, Pete Seeger wasn’t present for the meeting, and Dylan certainly didn’t get a harmonica. However, Dylan’s brief time with Guthrie did inspire “Song to Woody.”

The Pete Seeger Show

Dylan never crashed Pete Seeger’s (Ed Norton) television show, Rainbow Quest. Dylan did appear on a radio show hosted by Seeger not long after he arrived in New York, but never on Quest. And never with a Delta Blues singer named Jesse Moffette (played by real-life blues guitarist Big Bill Morganfield), as the character of Moffette is a total movie creation.

No Cash

While Boyd Holbrook’s Johnny Cash is a real hoot and a heat-check performance from one of Mangold’s favorite actors, Cash was never present at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Cash was present at the festival in 1964, where it’s possible the pair met. Otherwise, this is likely a nice bit of fan-fiction created by Mangold to tie Unknown to Walk to the Line and to give Holbrook a juicy little role.

Police Whistle

Ahead of the Highway 61 session, Dylan is seen purchasing a police whistle that would be included throughout the recording of the album. While the whistle is a critical part, Dylan’s role in securing it is overstated. Instead, organist Al Kooper had it and boasted to Rolling Stone that he kept it around his neck, often blowing on it in “certain situations, mostly related to drugs.” He also stated that he thought it “sounded great” and gave it to Dylan to play “instead of the harmonica.”

1965 Newport Folk Festival

The outrage over Dylan going electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival is only slightly blown out of proportion. The whole response to the event has taken on a life of its own, but we know a few things for certain. People were definitely not happy, but it’s hard to tell if that was because he went electric or because the music was simply too loud. Seeger later wrote to Dylan that he was “furious at the distorted sound,” which is why he ran over to the PA system and those controlling it. He also refutes the widely circulated story about wanting to axe it by simply telling the sound guys that if he had one, he would have used it.

Additionally, the “Judas!” moment didn’t happen in Newport, but a year later, in England. Dylan was playing a show at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester when a fan shouted it out. Dylan’s response? “Play it f***ing loud,” as he and the band proceeded right into “Like a Rolling Stone.”