A mammoth tusk boomerang from Poland is 40,000 years old

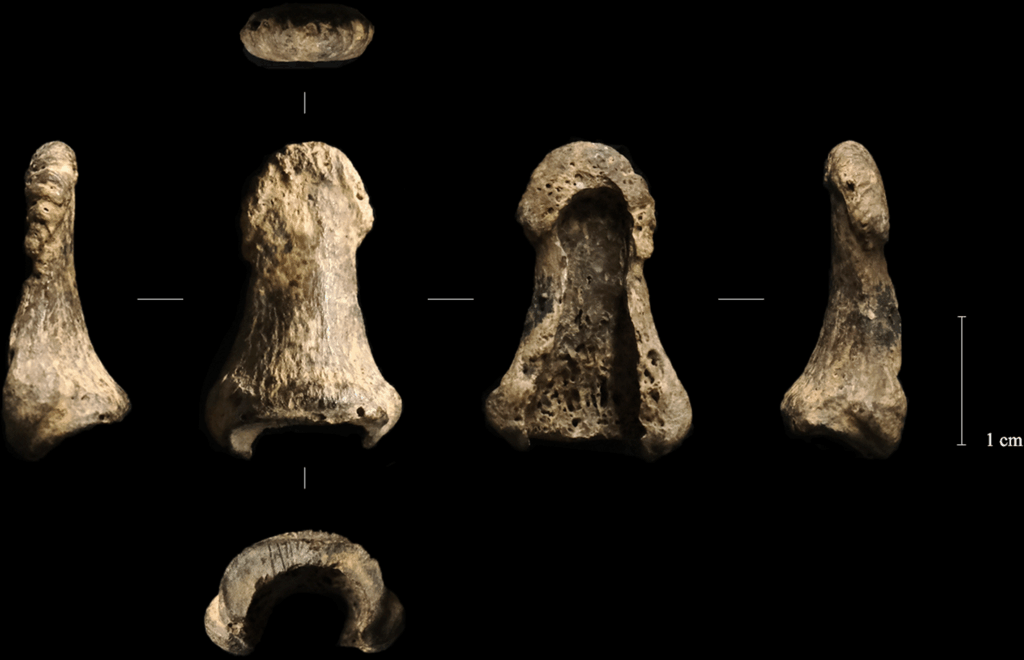

This left distal phalanx was found not far from the mammoth tusk boomerang.

Credit:

Talamo et al. 2025

What about the human thumb?

The human thumb-bone (or left distal phalanx, if you’re feeling fancy) is an intriguing part of the boomerang’s story. Archaeologists found the boomerang buried near a circle of boulders in the center of the cave chamber, buried alongside tools made from antlers, a pair of arctic fox-tooth pendants, a bone bead… oh, and the last bone from someone’s left thumb.

Talamo and her colleagues speculate that there was some kind of ritual involved (archaeologists in general are fond of such speculation, but there may be something to it in this case). The boulders “appear to have been transported from the nearby river and intentionally placed,” they write in their paper.

So not only is this a boomerang carved from a mammoth tusk, and not only does it apparently date to a period when most paleoanthropologists have thought central and northern Europe were largely deserted, but it may have been part of a ritual so ancient that we have no way of reconstructing its meaning or details.

Surviving in a prehistoric climatic wasteland

Archaeologists aren’t sure who invented boomerangs first, but at various times in human history, people on at least three continents seem to have thought to use a curved, flat stick that spins as it flies through the air to hit a target. Examples have been found in Africa, Australia, and Europe. In other words, boomerangs, like spears and bows, seem to be a frequent solution to the same basic problem: how to hit things with a stick.

Welcome to Oblazowa Cave, Poland.

Credit:

Talamo et al. 2025

Even at 18,000 years old, the mammoth boomerang was already among the oldest examples of spinning-flying-flat-stick technology (some might even have called it revolutionary) in the world. But with the updated age estimate, the Oblazowa Cave boomerang reveals some interesting things about the people who lived in what’s now Poland during the last Ice Age.

Until recently, it looked as though central and northern Europe lay uninhabited for thousands of years after the last Neanderthals either left or died out.