Archaeologists just mapped a Bronze Age megafortress in Georgia

pastoral nomads, please stop here

This recently mapped Bronze Age fortress is just one among hundreds.

This orthographic photo shows the inner fortress walls and some nearby structures.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

A sprawling 3,500-year-old fortress offers tantalizing clues about a culture that once dotted the southern Caucasus mountains with similar walled communities.

Archaeologists recently used a drone to map a sprawling 3,500-year-old fortress in the Caucasus Mountains of southern Georgia. The detailed aerial map offers some tantalizing clues about the ancient culture whose people built hundreds of similar fortresses in a mountainous region that spans the modern countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Based on their survey and excavations within the fortress walls, Cranfield University archaeologist Nathaniel Erb-Satullo and his colleagues suggest the fortified community may have been a place where nomadic herders converged during their yearly migration, but the evidence still leaves more questions than answers.

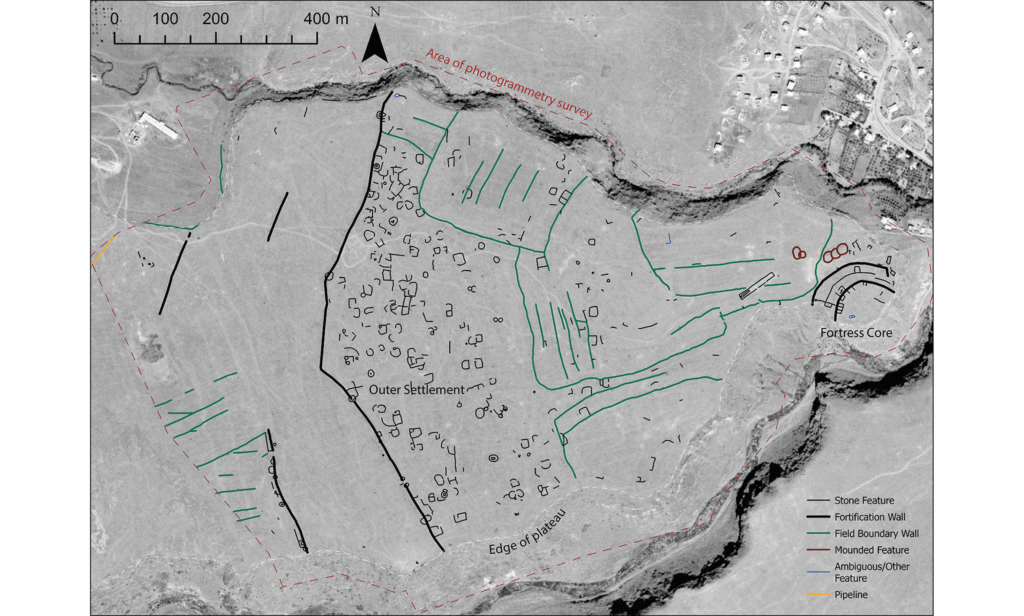

This map shows an aerial map of the ancient megafortress at Dmanisis Gora.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

An abandoned ancient megafortress

The half-buried Bronze Age ruins of Dmanisis Gora perch on a windswept promontory a few kilometers away from a cave where Homo erectus (or a close relative) lived 1.8 million years ago. Deep, steep-sided gorges run along two sides of the promontory, and sometime between 1500 and 1000 BCE, people stacked boulders into a double layer of high, thick walls to block off the end of the plateau from the plains to the west. Sheltered between the 4-meter high, 2.5-meter wide walls and the 60-meter-deep gorges, people built dugout houses, then later aboveground stone ones, along with stone animal pens and other buildings.

Outside the walls lay a more sprawling, less densely packed settlement, sheltered by another wall to the west. That outer wall was as high and wide as the inner ones, and it stretched a full kilometer from the edge of one gorge to the edge of the other. Between the walls, homes and other buildings formed small compounds with open space between them. Fenced fields, animal pens, and graves dotted the area.

Erb-Satullo and his colleagues recently mapped the whole fortress with their DJI Phantom 4 RTK drone. Eleven-thousand aerial images, stitched together with software into orthographic photos and digital elevation maps, revealed that the fortified community was much larger than the team had initially suspected. The innermost walls shelter an area of about 1.5 hectares, but the other wall encloses a total of 56. And a partial wall, which may have been destroyed in the past or simply started and never finished, would bring the total fortified area to around 80 hectares.

“Because of its size, it was impossible to get a sense of the site as a whole from the ground,” Erb-Satullo and his colleagues explain in a press release.

This aerial photo shows the outer fortress wall, with the outlines of several collapsed structures in the foreground, looking west.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

A world of fortresses and nomads

Although the fortress is huge—several times than the area of the nearby medieval town of Dmanisi, a major trading post during the Middle Ages that once boasted a cathedral and a castle—it’s just one of hundreds that dot the southern Caucasus mountains, most of which haven’t been surveyed or excavated in detail.

“These examples suggest that the Damanisis Gora mega-fortress, while exceptional in size, is not entirely without parallel,” write Erb-Satullo and his colleagues in their paper.

These fortresses tended to take advantage of features like gorges and hilltops for natural defenses, supplementing those with walls of unworked boulders stacked without mortar. Within the walls, crafters cast elaborate bronze work and made gray and black pottery burnished to a shine (though reds and buffs got more popular over time). They sewed using bone needles, and they wore beads of bone, carnelian, copper, and faience (a type of ceramic).

The people who lived and died in these walled communities buried their dead in mounds called kurgans, in massive stone-built tombs called cromlechs, or smaller stone-lined graves called cists (pronounced “kist”). One of these cist graves lies near the main gate of the inner fortress, “positioned such that anyone passing through the gate would have passed directly by it.” Its occupant went to the next life with beads, copper-alloy arrowheads, and pottery. In the inner and outer fortress, a mix of all three types of graves dot the area; there’s no defined graveyard to separate the dwellings of the dead from those of the living.

Smaller, narrower stone walls mark the boundaries of fields, both within and outside the walls of the fortified community. Some of those fields were plowed and fenced long after the fortress had crumbled into rubble; aerial photos reveal where plows tore into the foundations of ancient structures. But others may date to the Bronze Age and early Iron Age heyday of Dmanisis Gora.

A settlement of migrants?

For a large part of the community, however, making a living meant herding livestock, a life of constant migration between highland pastures in the summer and winter grazing in the lowlands.

Erb-Satullo and his colleagues are still trying to understand how the constant seasonal motion of pastoral herders relates to settled life behind stone walls. But at the moment, their best idea is that the area between the inner and outer walls may have been a seasonal settlement for herders passing through. Dmanisis Gora lies on the route ancient herders would have followed each spring and autumn.

“One possibility is that Dmanisis Gora served as a staging ground for pastoral groups during transitional periods in the spring and autumn,” write Erb-Satullo and his colleagues. In an earlier paper, following some excavations at the site in 2022, they suggested, “Its large outer settlement may have expanded and contracted seasonally.”

A seasonal stopover for migrating herders and their flocks may explain some puzzling quirks of the outer fortress. People went to the trouble of building stone buildings and pens, which suggests a permanent settlement rather than a temporary camp, but they didn’t leave behind many artifacts. In the innermost section of the fortress, archaeologists have unearthed two distinct layers of construction and discarded objects: tens of thousands of potsherds, beads, needles, and ritual items. But in the area between the innermost and outer walls, finds are sparse. That may mean that people stayed in the outer fortress regularly enough to justify stone buildings, but they probably didn’t stick around for very long.

That gave rise to the idea that the outer area may have been seasonal quarters for nomads, who took shelter behind the walls with their herds during the twice-yearly trek from lowland to highlands back again. To be sure, Erb-Satullo and his colleagues will need to study Dmanisis Gora more closely and make detailed maps of similar sites.

“With the site now extensively mapped, further study will start to provide insights into areas such as population density and intensity, livestock movements, and agricultural practices, among others,” says Erb-Satullo in a press release.

This orthographic photo shows the inner fortress walls and some nearby structures.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

A tale of resilience and ruin?

Another question on Erb-Satullo and his colleagues’ minds is how settlements like Dmanisis Gora weathered the Bronze Age collapse: a wave of invasions, famines, earthquakes, and economic and political upheaval that wreaked havoc on civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Nile Valley, and along the Mediterranean at the beginning of the 1100s BCE.

At Dmanisis Gora, radiocarbon dates and the types of pottery and construction suggest that life carried on without a hitch (or at least not one that shows up in the archaeological record so far) even as the rest of the world was violently transitioning from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. Erb-Satullo and his colleagues suggest that something about the blend of mobility and fortified settlement may have given the fortress-building people of the Caucasus some resilience against the tides of 12th-century collapse. But that’s another question that will ultimately require more evidence to answer.

Meanwhile, reminding us that no civilization—no matter how resilient—is actually permanent, the aerial photos reveal where plows had torn up the ruins of some ancient structures, long since collapsed. An abandoned barn on the site, built over what may once have been the homes of herders between pastures, fell into decay around the 1700s or 1800s CE, and fields where stone houses and graves once stood were being plowed and farmed during the Soviet era in 1972.

Antiquity, 2017. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.197 (About DOIs).