For some reason, NASA is treating Orion’s heat shield problems as a secret

“I’m not going to share right now. When it comes out, it’ll all come out together.”

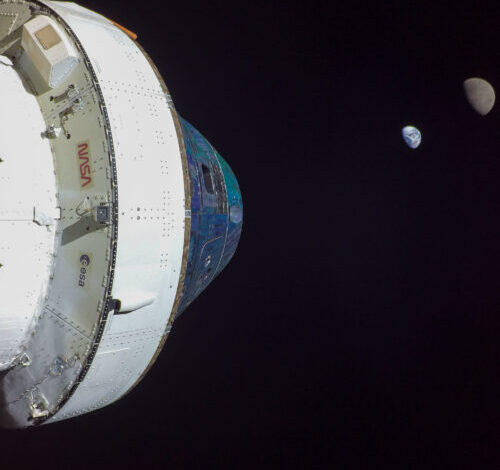

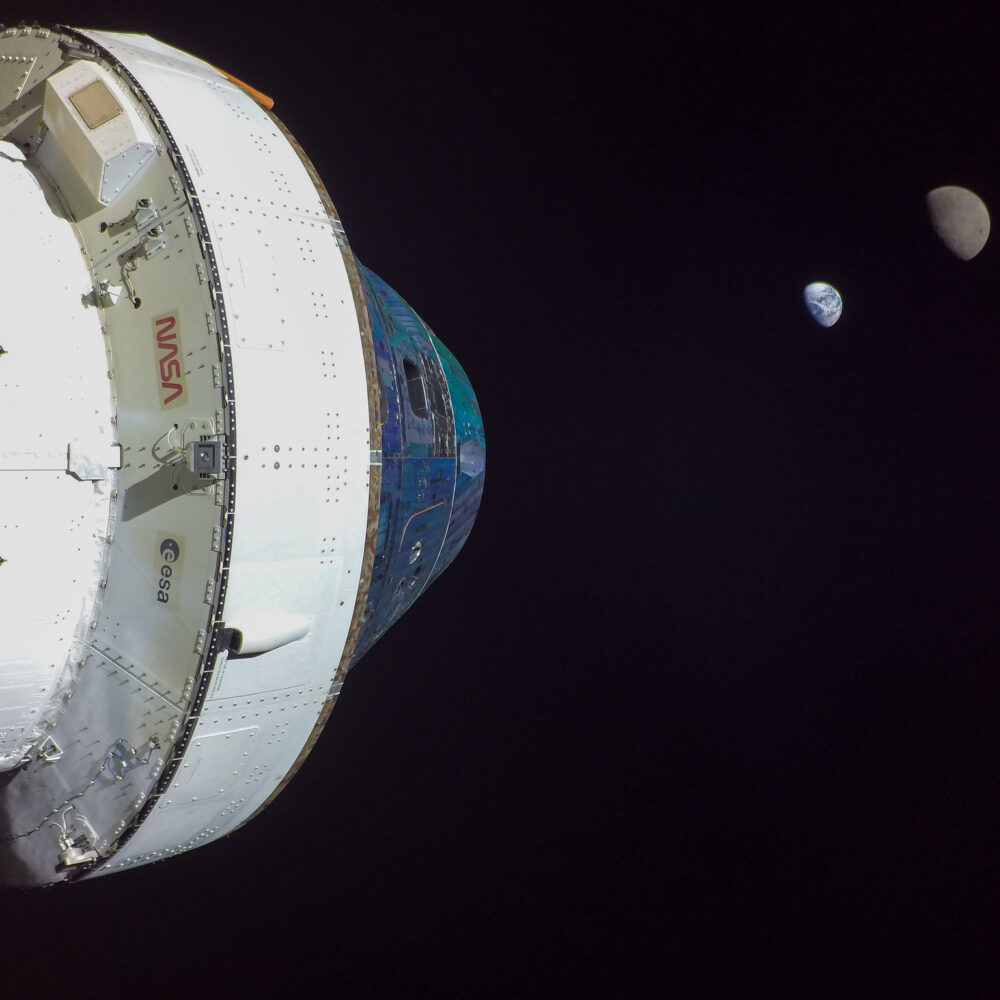

A photo from the Orion spacecraft on the Artemis I mission, showing the Moon and Earth suspended in the blackness of space.

For those who follow NASA’s human spaceflight program, when the Orion spacecraft’s heat shield cracked and chipped away during atmospheric reentry on the unpiloted Artemis I test flight in late 2022, what caused it became a burning question.

Multiple NASA officials said Monday they now know the answer, but they’re not telling. Instead, agency officials want to wait until more reviews are done to determine what this means for Artemis II, the Orion spacecraft’s first crew mission around the Moon, officially scheduled for launch in September 2025.

“We have gotten to a root cause,” said Lakiesha Hawkins, assistant deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Moon to Mars program office, in response to a question from Ars on Monday at the Wernher von Braun Space Exploration Symposium.

“We are having conversations within the agency to make sure that we have a good understanding of not only what’s going on with the heat shield, but also next steps and how that actually applies to the course that we take for Artemis II,” she said. “And we’ll be in a position to be able to share where we are with that hopefully before the end of the year.”

Conclusive determination

While the space program is far down the list of most voters’ priorities, this means a decision and announcement on what will happen with Artemis II won’t come until the post-election lame duck period in the waning weeks of the Biden administration, and likely Bill Nelson’s tenure as NASA administrator. This is several months later than NASA officials expected to make a decision.

The question here is whether NASA managers decide it is safe enough to fly the Orion heat shield as-is on Artemis II, or if it is too risky with people onboard. Artemis II will be a 10-day mission taking its four-person crew on a path around the far side of the Moon, then back to Earth. This will be the first time people travel to such distances since the Apollo program ended more than 50 years ago.

NASA’s Orion spacecraft descends toward the Pacific Ocean on December 11, 2022, at the end of the Artemis I mission.

Credit:

NASA

NASA’s Orion spacecraft descends toward the Pacific Ocean on December 11, 2022, at the end of the Artemis I mission.

Credit:

NASA

On Artemis I, the Orion spacecraft flew around the Moon for roughly three weeks, then returned to Earth for an on-target splashdown in the Pacific Ocean to wrap up a 25-day test flight. The heat shield, made of a material called Avcoat, was supposed to gradually and evenly burn away when the Orion spacecraft plunged into the atmosphere at a velocity of more than 24,500 mph (nearly 40,000 kmh), significantly faster than a capsule returning from low-Earth orbit. Artemis I was the first time the Orion crew capsule, built by Lockheed Martin, returned to Earth at such a speed from deep space.

Instead, the Avcoat material cracked unexpectedly, causing charred chunks to fall off the heat shield, and leaving cavities resembling potholes. The Orion spacecraft safely splashed down, and if astronauts had been inside, they would have been fine. However, the spacecraft didn’t perform the way engineers predicted, and demonstrating the function of the heat shield was one of the primary goals of the Artemis I mission. In the unforgiving world of human spaceflight, that should—and did—give engineers pause.

An internal investigation and an independent inquiry completed their probe of the cause of the heat shield erosion a couple of months ago.

“We have conclusive determination of what the root cause is of the issue,” said Lori Glaze, acting deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, which oversees the Artemis program aimed at returning US astronauts to the Moon.

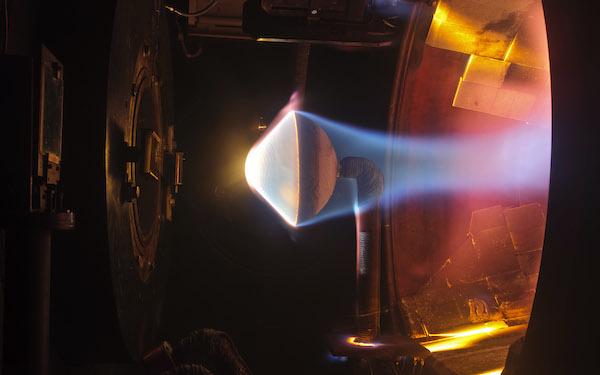

In a step further, she said engineers confirmed the root cause finding and reproduced the char loss with testing inside an arc jet facility at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. This facility can simulate the aero-thermodynamic heating a spacecraft endures during a hypersonic atmospheric entry. To do this, engineers use a test chamber with a continuous electrical arc to heat and expand gases to blistering temperatures, then direct the super-heated flow toward a test sample suspended in vacuum.

This capability makes the arc jet test facility unique in the world, but it still can’t fully replicate the stresses a spacecraft’s heat shield undergoes during reentry. There are some things that are just unknowable until you fly, said Victor Glover, pilot of the Artemis II mission, in an interview with Ars earlier this year.

File photo showing arc jet testing of a spacecraft’s heat shield at Ames Research Center.

Credit:

NASA

“What we are doing now is assessing what is the appropriate approach for Artemis II, regarding the heat shield,” Glaze said Monday. “We know what needs to be done for future missions, but the Artemis II heat shield is already built. So how do we assure astronaut safety with Artemis II?”

This will be the second major human spaceflight safety decision NASA will make this year, following the agency’s choice to conclude the first piloted test flight of Boeing’s commercial crew capsule without its astronauts in the cockpit. Instead, the capsule’s two-person crew remained behind at the International Space Station after NASA managers could not get comfortable with malfunctions in Starliner’s propulsion system.

They’re not saying

Speaking at a meeting of lunar scientists Monday, Glaze said NASA wants to complete additional testing before a final determination on what to do with Artemis II. The final decision, she said, will be made by NASA Administrator Bill Nelson.

“We expect that additional testing to conclude by the end of November, and then we anticipate discussions with the administrator, who will make the final decision on how to proceed,” Glaze said. “I know we all want more information faster, sooner, better. We’re moving it as quickly as it possibly can move, and there will be decisions forthcoming.”

An attendee of the lunar science meeting in Houston asked Glaze if she could share the root cause of the heat shield erosion. “I’m not going to share right now,” she replied. “When it comes out, it’ll all come out together.”

Ars also asked a NASA spokesperson for details on the root cause. The spokesperson confirmed the agency has determined the root cause, but declined to identify the cause, saying the information is “under review” as officials plot the path forward for Artemis II. The spokesperson echoed Hawkins’ statement that NASA will release more information before the end of the year.

NASA has not been a model for openness during the heat shield investigation. The agency first revealed the unexpected performance of the Orion heat shield in March 2023, four months after the end of the Artemis I mission.

It was only in May of this year, nearly a year and a half after Artemis I’s return to Earth, when NASA’s inspector general watchdog issued a report that included the first publicly available images of the Orion heat shield’s condition after splashdown.

The inspector general’s report May 1 included new images of Orion’s heat shield.

Credit:

NASA Inspector General

The inspector general’s report May 1 included new images of Orion’s heat shield.

Credit:

NASA Inspector General

Another report released by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in June said a preliminary analysis of the heat shield problem suggested to engineers that “the permeability of the material was lower than their models had indicated.”

“For Artemis II, officials said the current investigation is evaluating flight trajectories with new heat shield modeling to determine if this will be sufficient to address this issue,” the GAO said.

It wasn’t clear from the GAO’s report whether this issue was related to the design of the heat shield, or the way it was manufactured and installed. The Avcoat material, developed by Textron Systems and produced under license by Lockheed Martin, is attached to the base of the Orion spacecraft in 186 molded blocks laid on top of the heat shield’s underlying structure.

The Orion spacecraft is well along for the Artemis II mission. The Artemis II heat shield is already mounted on the bottom of the Orion crew capsule, which itself is mated to the top of Orion’s European-built service module. In order to make any changes to the heat shield, technicians would have to partially disassemble the spacecraft, fix it, then reconnect the spacecraft’s two main elements, and likely redo some of the preflight tests already completed on the vehicle.

This would inevitably delay the Artemis II mission a year or more. That is why engineers hope they can present data to convince managers and crew safety officials it is safe to fly the heat shield as-is. There are ways engineers can modulate the heating profile on the heat shield by adjusting the angle of the Orion spacecraft’s entry into the atmosphere at the end of the Artemis II mission. Ars discussed some of these options in a story published in May.

Reason to doubt

But the September 2025 target launch date for Artemis II is already in doubt for at least a couple of reasons.

One of those is that the indecision on what to do about the Artemis II heat shield has led NASA to postpone stacking of the Orion spacecraft’s rocket, the heavy-lift Space Launch System, at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. That was supposed to begin in September, a year before the planned launch, but NASA doesn’t want to begin assembling the SLS solid rocket boosters until there is a final answer on the Orion heat shield. Once stacking begins, there is a limit on how long the solid rocket boosters can remain standing on the mobile launch platform.

Another reason is a concern that ground systems at Kennedy Space Center won’t be ready to support the Artemis II launch in September of next year, according to a recent report by the Government Accountability Office.

In the long run, engineers may redesign or change their manufacturing methods to address the heat shield char loss concern for future Artemis missions. Lockheed Martin is on contract to deliver Orion capsules to NASA through the Artemis VIII mission. NASA will begin reusing Orion capsules beginning with Artemis VI, which won’t fly before the early 2030s.

Artemis III, officially scheduled for late 2026, is slated to be the program’s first lunar landing mission. The first Artemis landing mission is all but certain to move later in the decade as NASA and its contractors develop a human-rated lunar lander and new spacesuits for astronauts to wear on the Moon.

If Orion design changes are in order, this might also impact the Artemis III schedule. It would be the second redesign of the Orion spacecraft’s heat shield. NASA and Lockheed Martin originally intended for Orion’s heat shield to be monolithic, or installed as a single unit, as it was for the Apollo command module that went to the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

After the Orion spacecraft’s first test flight in Earth orbit in 2014, managers switched the heat shield to the block architecture used on Artemis I.