Greening of Antartica shows how climate change affects the frozen continent

Plant growth is accelerating on the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby islands.

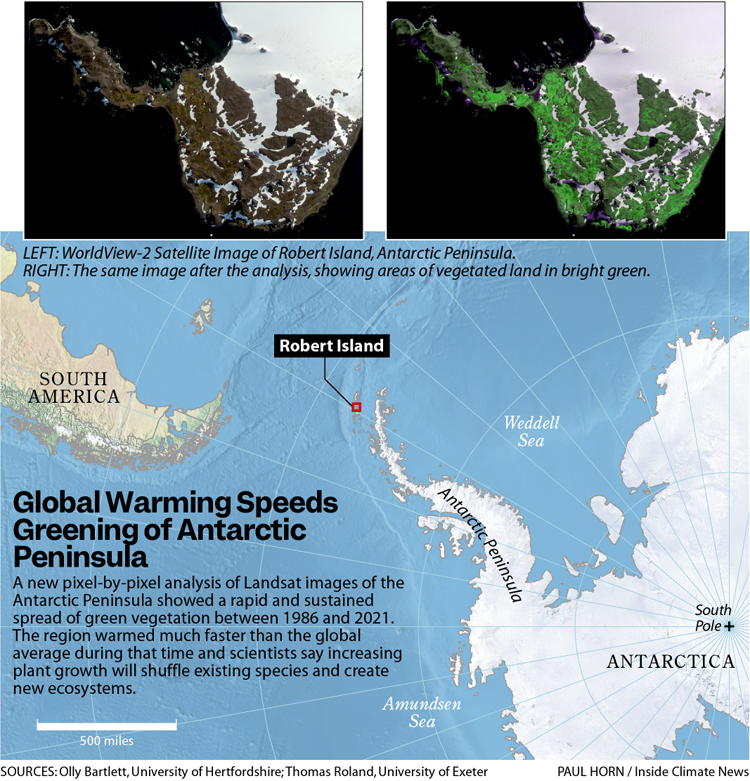

When satellites first started peering down on the craggy, glaciated Antarctic Peninsula about 40 years ago, they saw only a few tiny patches of vegetation covering a total of about 8,000 square feet—less than a football field.

But since then, the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed rapidly, and a new study shows that mosses, along with some lichen, liverworts and associated algae, have colonized more than 4.6 square miles, an area nearly four times the size of New York’s Central Park.

The findings, published Friday in Nature Geoscience, based on a meticulous analysis of Landsat images from 1986 to 2021, show that the greening trend is distinct from natural variability and that it has accelerated by 30 percent since 2016, fast enough to cover nearly 75 football fields per year.

Greening at the opposite end of the planet, in the Arctic, has been widely studied and reported, said co-author Thomas Roland, a paleoecologist with the University of Exeter who collects and analyzes mud samples to study environmental and ecological change. “But the idea,” he said, “that any part of Antarctica could, in any way, be green is something that still really jars a lot of people.”

Credit:

Inside Climate News

As the planet heats up, “even the coldest regions on Earth that we expect and understand to be white and black with snow, ice, and rock are starting to become greener as the planet responds to climate change,” he said.

The tenfold increase in vegetation cover since 1986 “is not huge in the global scheme of things,” Roland added, but the accelerating rate of change and the potential ecological effects are significant. “That’s the real story here,” he said. “The landscape is going to be altered partially because the existing vegetation is expanding, but it could also be altered in the future with new vegetation coming in.”

In the Arctic, vegetation is expanding on a scale that affects the albedo, or the overall reflectivity of the region, which determines the proportion of the sun’s heat energy that is absorbed by the Earth’s surface as opposed to being bounced away from the planet. But the spread of greenery has not yet changed the albedo of Antarctica on a meaningful scale because the vegetated areas are still too small to have a regional impact, said co-author Olly Bartlett, a University of Hertfordshire researcher who specializes in using satellite data to map environmental change.

“The real significance is about the ecological shift on the exposed land, the land that’s ice-free, creating an area suitable for more advanced plant life or invasive species to get a foothold,” he said.

Bartlett said Google Earth Engine enabled the scientists to process a massive amount of data from the Landsat images to meet a high standard of verification of plant growth. As a result, he added, the changes they reported may actually be conservative.

“It’s becoming easier for life to live there,” he said. “These rates of change we’re seeing made us think that perhaps we’ve captured the start of a more dramatic transformation.”

In the areas they studied, changes to the albedo could have a small local effect, Roland said, as more land free of reflective ice “can feed into a positive feedback loop that creates conditions that are more favorable for vegetation expansion as well.”

Antarctic forests at similar CO2 levels

Other research, including fossil studies, suggests that beech trees grew on Antarctica as recently as 2.5 million years ago, when carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere were similar to today, another indicator of how unchecked greenhouse gas emissions can rapidly warm Earth’s climate.

Currently, there are only two species of flowering plants native to the Antarctic Peninsula, Antarctic hair grass, and Antarctic pearlwort. “But with a few new grass seeds here and there, or a few spores, and all of a sudden, you’ve got a very different ecosystem,” he said.

And it’s not just plants, he added. “Increasingly, we’re seeing evidence that non-native insect life is taking hold in Antarctica. And that can dramatically change things as well.”

The study shows how climate warming will shake up Antarctic ecosystems, said conservation scientist Jasmine Lee, a research fellow with the British Antarctic Survey who was not involved in the new study.

“It is clear that bank-forming mosses are expanding their range with warmer and wetter conditions, which is likely facilitating similar expansions for some of the invertebrate communities that rely on them for habitat,” she said. “At the same time, some specialist species, such as the more dry-loving mosses and invertebrates, might decline.”

She said the new study is valuable because it provides data across a broad region showing that Antarctic ecosystems are already rapidly altering and will continue to do so as climate change progresses.

“We focus a lot on how climate change is melting ice sheets and changing sea ice,” she said. “It’s good to also highlight that the terrestrial ecosystems are being impacted.”

The study shows climate impacts growing in “regions previously thought nearly immune to the accelerated warming we’re seeing today,” said climate policy expert Pam Pearson, director of the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative.

“It’s as important a signal as the loss of Antarctic sea ice over the past several years,” she said.

The new study identified vegetative changes by comparing the Landsat images at a resolution of 300-square-feet per pixel, detailed enough to accurately map vegetative growth, but it didn’t identify specific climate change factors that might be driving the expansion of plant life.

But other recent studies have documented Antarctic changes that could spur plant growth, including how some regions are affected by warm winds and by increasing amounts of rain from atmospheric rivers, as well as by declining sea ice that leads adjacent land areas to warm, all signs of rapid change in Antarctica.

Roland said their new study was in part spurred by previous research showing how fast patches of Antarctic moss were growing vertically and how microbial activity in tiny patches of soil was also accelerating.

“We’d taken these sediment cores, and done all sorts of analysis, including radiocarbon dating … showing the growth in the plants we’d sampled increasing dramatically,” he said.

Those measurements confirmed that the plants are sensitive to climate change, and as a next step, researchers wanted to know “if the plants are growing sideways at the same dramatic rate,” he said. “It’s one thing for plants to be growing upwards very fast. If they’re growing outwards, then you know you’re starting to see massive changes and massive increases in vegetation cover across the peninsula.”

With the study documenting significant horizontal expansion of vegetation, the researchers are now studying how recently deglaciated areas were first colonized by plants. About 90 percent of the glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula have been shrinking for the past 75 years, Roland said.

“That’s just creating more and more land for this potentially rapid vegetation response,” he said. “So like Olly says, one of the things we can’t rule out is that this really does increase quite dramatically over the next few decades. Our findings raise serious concerns about the environmental future of the Antarctic Peninsula and of the continent as a whole.”

This story originally appeared on Inside Climate News.

-

1.

Helene ravaged the NC plant that makes 60% of the country’s IV fluid supply

-

2.

Apple couldn’t tell fake iPhones from real ones, lost $2.5M to scammers

-

3.

Neo-Nazis head to encrypted SimpleX Chat app, bail on Telegram

-

4.

Halls of Torment is Diablo cranked up to 50,000 kills/hour

-

5.

X fails to avoid Australia child safety fine by arguing Twitter doesn’t exist