Kurt Vonnegut’s lost board game published

Fans of literature most likely know Kurt Vonnegut for the novel Slaughterhouse-Five. The staunchly anti-war book first resonated with readers during the Vietnam War era, later becoming a staple in high school curricula the world over. When Vonnegut died in 2007 at the age of 84, he was widely recognized as one of the greatest American novelists of all time. But would you believe that he was also an accomplished game designer?

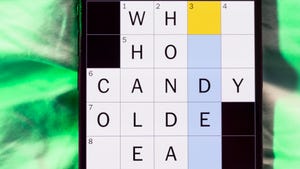

In 1956, following the lukewarm reception of his first novel, Player Piano, Vonnegut was one of the 16 million other World War II veterans struggling to put food on the table. His moneymaking solution at the time was a board game called GHQ, which leveraged his understanding of modern combined arms warfare and distilled it into a simple game played on an eight-by-eight grid. Vonnegut pitched the game relentlessly to publishers all year long according to game designer and NYU faculty member Geoff Engelstein, who recently found those letters sitting in the archives at Indiana University. But the real treasure was an original set of typewritten rules, complete with Vonnegut’s own notes in the margins.

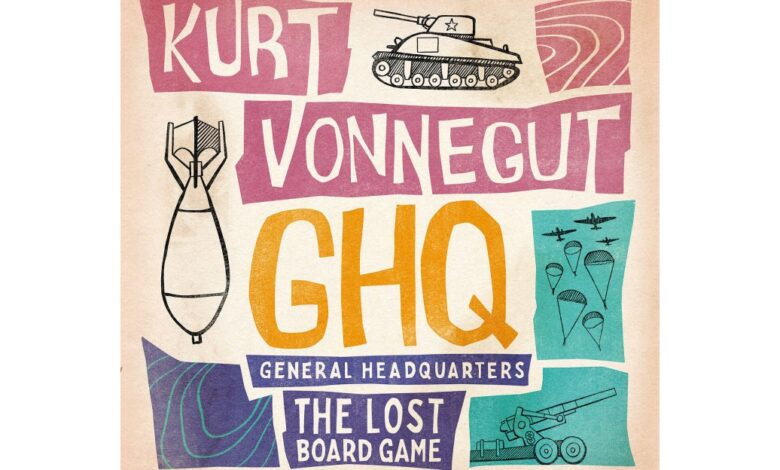

With the permission of the Vonnegut estate, Engelstein tells Polygon that he cleaned the original rules up just a little bit, buffed out the dents in GHQ’s endgame, and spun up some decent art and graphic design. Now you can purchase the final product, titled Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ: The Lost Board Game, at your local Barnes & Noble — nearly 70 years after it was created.

In a recent interview with Polygon, Engelstein still seemed stunned to have stumbled over the game in the first place through his research. But what’s truly fascinating to him is how diametrically opposed to Vonnegut’s later work GHQ truly is.

“Sirens of Titan was written at the same time as he was working on this game,” Engelstein told Polygon. “In Sirens of Titan, there’s this army of Mars which is really a joke. No one in the army, [not] even the officers, are really in charge of what’s going on. They’re all mind controlled. Nobody has any real free will. They’re just set up as a pawn to be sacrificed, to make Earth come together, kind of Watchmen-style.”

While The Sirens of Titan was a deeply cynical view of war, GHQ is deeply uncynical. In fact, his own pitch letters note that Vonnegut thought GHQ would be an excellent training aid for future military leaders, including cadets at West Point. How are modern audiences to reconcile those words from the same man who wrote Cat’s Cradle?

“There’s no definitive answers [to those questions],” Engelstein said. “He didn’t write about it. Nobody asked him about it while he was alive, so we will never know.”

For fans of board gaming, the questions go in a slightly different direction: What if Vonnegut’s pitches from the 1950s had been successful?

Engelstein reasons that if Vonnegut was pitching the game in ’56, then it would have taken at least a few years for the game to be produced and finally published. That 1958-1959 window would have placed GHQ in rare company — 1958 was the year Tactics 2 was published, a game that would go on to inspire the Squad Leader series of map-and-token tactical wargames and, ultimately, video game genres like turn-based and real-time strategy. Just a year later and the industry would see the release of Risk and Diplomacy, the precursors of the modern 4X genre and, in and of themselves, two successful franchises that are popular to this day.

“Three games that had tremendous influence, all war-related, coming out in that one-year, two-year period,” Engelstein mused. “So if GHQ also came out at the time period? There’s something in the air at that point, obviously.”

Of course, we’ll never know how those counterfactuals would have played out, but at least GHQ is finally available to the public. That’s great news for one of its original playtesters, Kurt Vonnegut’s son, Mark Vonnegut, who’s now 77. Engelstein said his input was invaluable in bringing the game to life.

“The success of Slaughterhouse-Five and the other novels is nice enough,” Vonnegut’s son recently wrote Engelstein in an email, “but I truly believe he’s watching somehow, someway, from somewhere and that the success of GHQ will be a greater and purely unadulterated pleasure. […] He was discouraged about his writing at the time, but had unshakable faith that GHQ would succeed.”

You can find Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ: The Lost Board Game, along with a special forward by author James S.A. Corey, exclusively at Barnes & Noble.