The One Billion Row Challenge in Go: from 1m45s to 4s in nine solutions

March 2024

Go to: Baseline | Solutions | Table of results | Final comments

I saw the One Billion Row Challenge a couple of weeks ago, and it thoroughly nerd-sniped me, so I went to Go solve it.

I’m late to the party, as the original competition was in January. It was also in Java. I’m not particularly interested in Java, but I’ve been interested in optimising Go code for a while.

This challenge was particularly simple: process a text file of weather station names and temperatures, and for each weather station, print out the minimum, mean, and maximum. There are a few other constraints to make it simpler, though I ignored the Java-specific ones.

Here are a few lines of example input:

Hamburg;12.0

Bulawayo;8.9

Palembang;38.8

St. John's;15.2

Cracow;12.6

...

The only catch: the input file has one billion rows (lines). That’s about 13GB of data. I’ve already figured out that disk I/O is no longer the bottleneck – it’s usually memory allocations and parsing that slow things down in a program like this.

This article describes the nine solutions I wrote in Go, each faster than the previous. The first, a simple and idiomatic solution, runs in 1 minute 45 seconds on my machine, while the last one runs in about 4 seconds. As I go, I’ll show how I used Go’s profiler to see where the time was being spent.

The run-down of solutions is as follows, slowest to fastest:

- r1: simple and idiomatic

- r2: map with pointer values

- r3: parse temperatures by hand

- r4: fixed point integers

- r5: avoid

bytes.Cut - r6: avoid

bufio.Scanner - r7: custom hash table

- r8: parallelise r1

- r9: parallelise r7

I wanted each of the solutions to be portable Go using only the standard library: no assembly, no unsafe, and no memory-mapped files. And 4 seconds, or 3.2GB/s, was fast enough for me. For comparison, the fastest, heavily-optimised Java solution runs in just under a second on my machine – not bad!

There are several other Go solutions out there already, and at least one nice write-up. Mine is faster than some solutions, but slightly slower than the fastest one. However, I didn’t look at any of these before writing mine – I wanted my solutions to be independent.

If you just care about the numbers, skip down to the table of results.

Baseline

Here are a few different baseline measurements to set the stage. First, how long does it take to just read 13GB of data, using cat:

$ time cat measurements.txt >/dev/null

0m1.052s

Note that that’s a best-of-five measurement, so I’m allowing the file to be cached. Who knows whether Linux will allow all 13GB to be kept in disk cache, though presumably it does, because the first time it took closer to 6 seconds.

For comparison, to actually do something with the file is significantly slower: wc takes almost a minute:

$ time wc measurements.txt

1000000000 1179173106 13795293380 measurements.txt

0m55.710s

For a simple solution to the actual problem, I’d probably start with AWK. This solution uses Gawk, because sorting the output is easier with its asorti function. I’m using the -b option to use “characters as bytes” mode, which makes things a bit faster:

$ time gawk -b -f 1brc.awk measurements.txt >measurements.out

7m35.567s

I’m sure I can beat 7 minutes with even a simple Go solution, so let’s start there.

I’m going to start by optimising the sequential, single-core version (solutions 1-7), and then parallelise it (solutions 8 and 9). All my results are done using Go 1.21.5 on a linux/amd64 laptop with a fast SSD drive and 32GB of RAM.

Many of my solutions, and most of the fastest solutions, assume valid input. For example, that the temperatures have exactly one decimal digit. Several of my solutions will cause a runtime panic, or produce incorrect output, if the input isn’t valid.

Solution 1: simple and idiomatic Go

I wanted my first version to be simple, straight-forward code using the tools in the Go standard library: bufio.Scanner to read the lines, strings.Cut to split on the ';', strconv.ParseFloat to parse the temperatures, and an ordinary Go map to accumulate the results.

I’ll include this first solution in full (but after that, show only the interesting bits):

func r1(inputPath string, output io.Writer) error {

type stats struct {

min, max, sum float64

count int64

}

f, err := os.Open(inputPath)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer f.Close()

stationStats := make(map[string]stats)

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

for scanner.Scan() {

line := scanner.Text()

station, tempStr, hasSemi := strings.Cut(line, ";")

if !hasSemi {

continue

}

temp, err := strconv.ParseFloat(tempStr, 64)

if err != nil {

return err

}

s, ok := stationStats[station]

if !ok {

s.min = temp

s.max = temp

s.sum = temp

s.count = 1

} else {

s.min = min(s.min, temp)

s.max = max(s.max, temp)

s.sum += temp

s.count++

}

stationStats[station] = s

}

stations := make([]string, 0, len(stationStats))

for station := range stationStats {

stations = append(stations, station)

}

sort.Strings(stations)

fmt.Fprint(output, "{")

for i, station := range stations {

if i > 0 {

fmt.Fprint(output, ", ")

}

s := stationStats[station]

mean := s.sum / float64(s.count)

fmt.Fprintf(output, "%s=%.1f/%.1f/%.1f", station, s.min, mean, s.max)

}

fmt.Fprint(output, "}n")

return nil

}

This basic solution processes the one billion rows in 1 minute and 45 seconds. A definite improvement over 7 minutes for the AWK solution.

Solution 2: map with pointer values

I’d learned doing my count-words program that we’re doing a bunch more hashing than we need to. For each line, we’re hashing the string twice: once when we try to fetch the value from the map, and once when we update the map.

To avoid that, we can use a map[string]*stats (pointer values) and update the pointed-to struct, instead of a map[string]stats and updating the hash table itself.

However, I first wanted to confirm that using the Go profiler. It only takes a few lines to add CPU profiling to a Go program.

$ ./go-1brc -cpuprofile=cpu.prof -revision=1 measurements-10000000.txt >measurements-10000000.out

Processed 131.6MB in 965.888929ms

$ go tool pprof -http=: cpu.prof

...

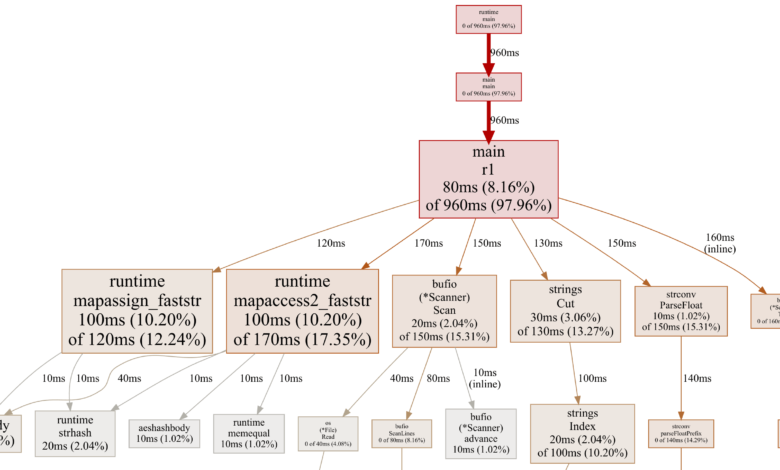

Those commands produced the following profile of solution 1, run over a cut-down 10 million row input file:

Map operations are taking a full 30% of the time: 12.24% for assign and 17.35% for lookup. We should be able to get rid of most of the map assign time by using a pointer value.

As a side note, this profile image also shows us where all the rest of the time is going:

- Scanning lines with

Scanner.Scan - Finding the

';'withstrings.Cut - Parsing the temperature with

strconv.ParseFloat - Calling

Scanner.Text, which allocates a string for the line

In any case, my second solution is just a small tweak to the map operations:

stationStats := make(map[string]*stats)

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

for scanner.Scan() {

// ...

s := stationStats[station]

if s == nil {

stationStats[station] = &stats{

min: temp,

max: temp,

sum: temp,

count: 1,

}

} else {

s.min = min(s.min, temp)

s.max = max(s.max, temp)

s.sum += temp

s.count++

}

}

In the common case where the station exists in the map, we now only do one map operation, s := stationStats[station], so that hashing the station name and accessing the hash table only has to be done once. If it’s in the map already – the common case in one billion rows – we update the existing pointed-to struct.

It doesn’t help a ton, but it is something: using pointer values in the map takes our time down from 1 minute 45 seconds to 1 minute 31 seconds.

Solution 3: avoid strconv.ParseFloat

My third solution is where things get a bit more hard-core: parse the temperature using custom code instead of strconv.ParseFloat. The standard library function handles a ton of edge cases we don’t need to support for the simple temperatures our input has: 2 or 3 digits in the format 1.2 or 34.5 (and some with a minus sign in front).

Also, strconv.ParseFloat took a string argument, and now that we’re no longer calling that, we can get away with using the byte slice directly from Scanner.Bytes, instead of allocating and copying a string with Scanner.Text.

Now we parse the temperature this way:

negative := false

index := 0

if tempBytes[index] == '-' {

index++

negative = true

}

temp := float64(tempBytes[index] - '0') // parse first digit

index++

if tempBytes[index] != '.' {

temp = temp*10 + float64(tempBytes[index]-'0') // parse optional second digit

index++

}

index++ // skip '.'

temp += float64(tempBytes[index]-'0') / 10 // parse decimal digit

if negative {

temp = -temp

}

Not pretty, but not exactly rocket science either. This gets our time down from to 1 minute 31 seconds to under a minute: 55.8 seconds.

Solution 4: fixed point integers

Back in the olden days, floating point instructions were a lot slower than integer ones. These days, they’re only a little slower, but it’s probably worth avoiding them if we can.

For this problem, each temperature has a single decimal digit, so it’s easy to use fixed point integers to represent them. For example, we can represent 34.5 as the integer 345. Then at the end, just before we print out the results, we convert them back to floats.

So my fourth solution is basically the same as solution 3, but with the stats struct field as follows:

type stats struct {

min, max, count int32

sum int64

}

Then, when printing out the results, we need to divide by 10:

mean := float64(s.sum) / float64(s.count) / 10

fmt.Fprintf(output, "%s=%.1f/%.1f/%.1f",

station, float64(s.min)/10, mean, float64(s.max)/10)

I’ve used 32-bit integers for minimum and maximum temperatures, as the highest we’ll probably have is about 500 (50 degrees Celsius). We could use int16, but from previous experience, modern 64-bit CPUs are slightly slower when handling 16-bit integers than 32-bit ones. In my tests just now it didn’t seem to make a measurable difference, but I opted for 32-bit anyway.

Using integers cut the time down from 55.8 seconds to 51.0 seconds, a small win.

Solution 5: avoid bytes.Cut

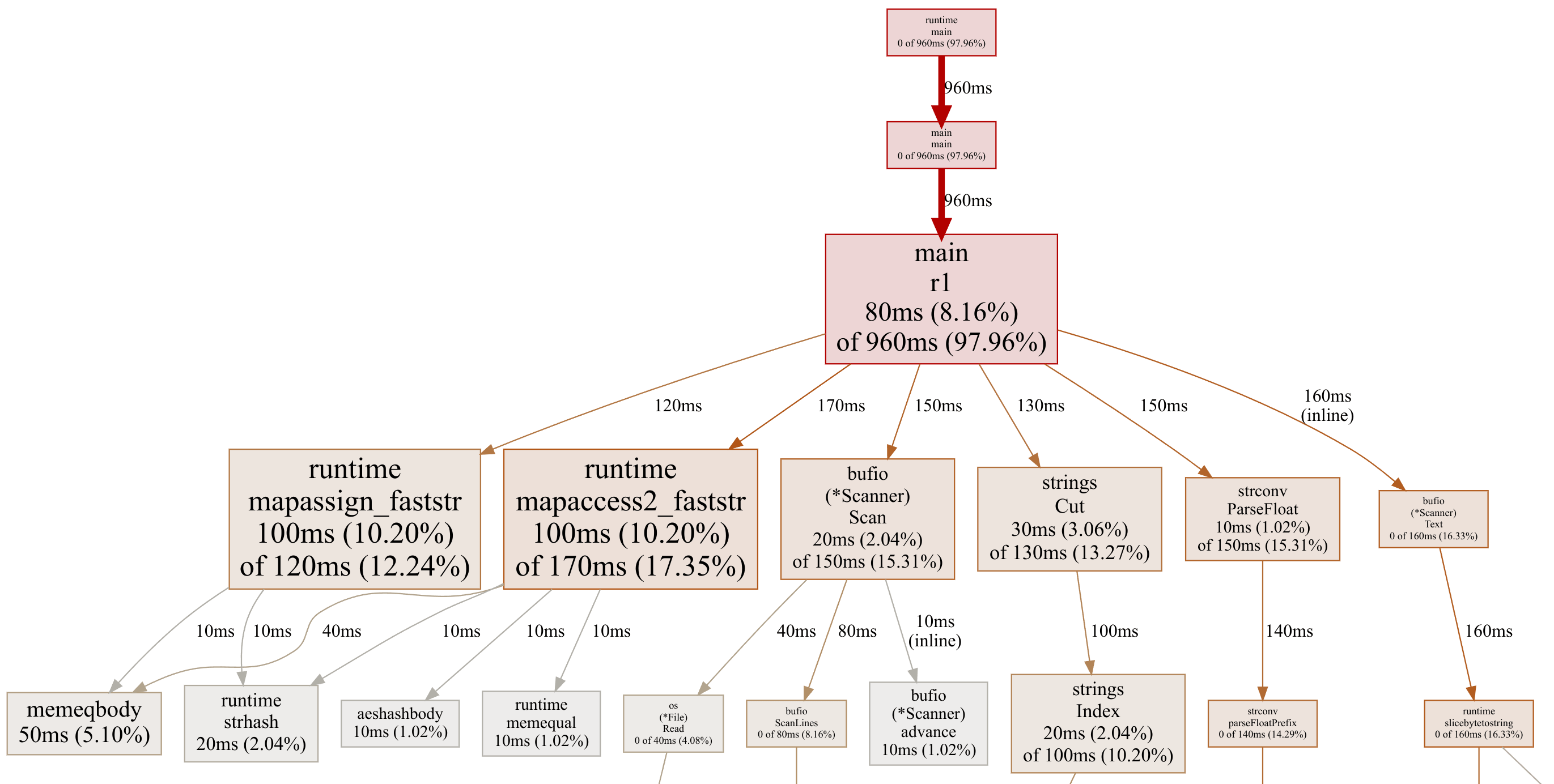

To make solution 5 I recorded another profile (of solution 4):

Okay, now it’s getting harder. The map operations dominate, and moving to a custom hash table will be a bit tricky. So will getting rid of the bufio.Scanner. Let’s procrastinate and get rid of the bytes.Cut.

I thought of a simple way to save time. If we look at a line, for example:

It’s going to be faster to parse the temperature from the end and find the ';' there than to scan through the whole station name to look for the ';'. This rather ugly code does just that:

end := len(line)

tenths := int32(line[end-1] - '0')

ones := int32(line[end-3] - '0') // line[end-2] is '.'

var temp int32

var semicolon int

if line[end-4] == ';' { // positive N.N temperature

temp = ones*10 + tenths

semicolon = end - 4

} else if line[end-4] == '-' { // negative -N.N temperature

temp = -(ones*10 + tenths)

semicolon = end - 5

} else {

tens := int32(line[end-4] - '0')

if line[end-5] == ';' { // positive NN.N temperature

temp = tens*100 + ones*10 + tenths

semicolon = end - 5

} else { // negative -NN.N temperature

temp = -(tens*100 + ones*10 + tenths)

semicolon = end - 6

}

}

station := line[:semicolon]

Avoiding bytes.Cut cut the time down from 51.0 seconds to 46.0 seconds, another small win.

Solution 6: avoid bufio.Scanner

Now we’re going to try to get rid of the bufio.Scanner. If you think about it, to find the end of each line, the scanner has to look through all the bytes to find the newline character. Then we process many of the bytes again to parse the temperature and find the ';'. So let’s try to combine those steps and throw bufio.Scanner out the window.

In solution 6 we allocate a 1MB buffer to read the file in large chunks, look for the last newline in the chunk to ensure we’re not chopping a line in half, and then process each chunk. That looks like this:

buf := make([]byte, 1024*1024)

readStart := 0

for {

n, err := f.Read(buf[readStart:])

if err != nil && err != io.EOF {

return err

}

if readStart+n == 0 {

break

}

chunk := buf[:readStart+n]

newline := bytes.LastIndexByte(chunk, 'n')

if newline < 0 {

break

}

remaining := chunk[newline+1:]

chunk = chunk[:newline+1]

for {

station, after, hasSemi := bytes.Cut(chunk, []byte(";"))

// ... from here, same temperature processing as r4 ...

Removing bufio.Scanner and doing our own scanning cut down the time from 46.0 seconds to 41.3 seconds. Yet another small win, but I’ll take it.

Solution 7: custom hash table

Solution 7 is where we get real. We’re going to implement a custom hash table instead of using Go’s map. This has two advantages:

- We can hash the station name as we look for the

';', avoiding processing bytes twice. - We can store each key in our hash table as a byte slice, avoiding the need to convert each key to a

string(which will allocate and copy for every line).

I’ve written about how to implement a hash table in C, but I’ve also implemented a custom “counter” hash table in Go, which is where I pulled this implementation from.

It’s a simple implementation that uses the FNV-1a hash algorithm with linear probing: if there’s a collision, use the next empty slot.

To simplify, I just pre-allocate a large number of hash buckets (I’ve used 100,000), to avoid having to write logic to resize the table. My code will panic if the table gets more than half full. I measured that we get around 2% hash collisions.

It’s a bunch more code this time – hash table setup, the hashing itself, and the table probing and insertion:

// The hash table structure:

type item struct {

key []byte

stat *stats

}

items := make([]item, 100000) // hash buckets, linearly probed

size := 0 // number of active items in items slice

buf := make([]byte, 1024*1024)

readStart := 0

for {

// ... same chunking as r6 ...

for {

const (

// FNV-1 64-bit constants from hash/fnv.

offset64 = 14695981039346656037

prime64 = 1099511628211

)

// Hash the station name and look for ';'.

var station, after []byte

hash := uint64(offset64)

i := 0

for ; i < len(chunk); i++ {

c := chunk[i]

if c == ';' {

station = chunk[:i]

after = chunk[i+1:]

break

}

hash ^= uint64(c) // FNV-1a is XOR then *

hash *= prime64

}

if i == len(chunk) {

break

}

// ... same temperature parsing as r6 ...

// Go to correct bucket in hash table.

hashIndex := int(hash & uint64(len(items)-1))

for {

if items[hashIndex].key == nil {

// Found empty slot, add new item (copying key).

key := make([]byte, len(station))

copy(key, station)

items[hashIndex] = item{

key: key,

stat: &stats{

min: temp,

max: temp,

sum: int64(temp),

count: 1,

},

}

size++

if size > len(items)/2 {

panic("too many items in hash table")

}

break

}

if bytes.Equal(items[hashIndex].key, station) {

// Found matching slot, add to existing stats.

s := items[hashIndex].stat

s.min = min(s.min, temp)

s.max = max(s.max, temp)

s.sum += int64(temp)

s.count++

break

}

// Slot already holds another key, try next slot (linear probe).

hashIndex++

if hashIndex >= len(items) {

hashIndex = 0

}

}

}

readStart = copy(buf, remaining)

}

The payoff for all this code is large: the custom hash table cuts down the time from 41.3 seconds to 25.8s.

Solution 8: process chunks in parallel

In solution 8 I wanted to add some parallelism. However, I thought I’d go back to the simple and idiomatic code from my first solution, which uses bufio.Scanner and strconv.ParseFloat, and parallelise that. Then we can see whether optimising or parallelising gives better results – and in solution 9 we’ll do both.

It’s straight-forward to parallelise a map-reduce problem like this: split the file into similar-sized chunks (one for each CPU core), fire up a thread (in Go, a goroutine) to process each chunk, and then merge the results at the end.

Here’s what that looks like at a high level:

// Determine non-overlapping parts for file split (each part has offset and size).

parts, err := splitFile(inputPath, maxGoroutines)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Start a goroutine to process each part, returning results on a channel.

resultsCh := make(chan map[string]r8Stats)

for _, part := range parts {

go r8ProcessPart(inputPath, part.offset, part.size, resultsCh)

}

// Wait for the results to come back in and aggregate them.

totals := make(map[string]r8Stats)

for i := 0; i < len(parts); i++ {

result := <-resultsCh

for station, s := range result {

ts, ok := totals[station]

if !ok {

totals[station] = r8Stats{

min: s.min,

max: s.max,

sum: s.sum,

count: s.count,

}

continue

}

ts.min = min(ts.min, s.min)

ts.max = max(ts.max, s.max)

ts.sum += s.sum

ts.count += s.count

totals[station] = ts

}

}

The splitFile function is a bit tedious, so I won’t include it here. It looks at the size of the file, divides that by the number of parts we want, and then seeks to each part, reading 100 bytes before the end and looking for the last newline to ensure each part ends with a full line.

The r8ProcessPart function is basically the same as the r1 solution, but it starts by seeking to the part offset and limiting the length to the part size (using io.LimitedReader). When it’s done, it sends its own stats map back on the channel:

func r8ProcessPart(inputPath string, fileOffset, fileSize int64,

resultsCh chan map[string]r8Stats) {

file, err := os.Open(inputPath)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer file.Close()

_, err = file.Seek(fileOffset, io.SeekStart)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

f := io.LimitedReader{R: file, N: fileSize}

stationStats := make(map[string]r8Stats)

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(&f)

for scanner.Scan() {

// ... same processing as r1 ...

}

resultsCh <- stationStats

}

Processing the input file in parallel provides a huge win over r1, taking the time from 1 minute 45 seconds to 24.3 seconds. For comparison, the previous “optimised non-parallel” version, solution 7, took 25.8 seconds. So for this case, parallelisation is a bit faster than optimisation – and quite a bit simpler.

Solution 9: all optimisations plus parallelisation

For solution 9, our last attempt, we’ll simply combine all the previous optimisations from r1 through r7 with the parallelisation we did in r8.

I’ve used the same splitFile function from r8, and the rest of the code is just copied from r7, so there’s nothing new to show here. Except the results … this final version cut down the time from 24.3 seconds to 3.99 seconds, a huge win.

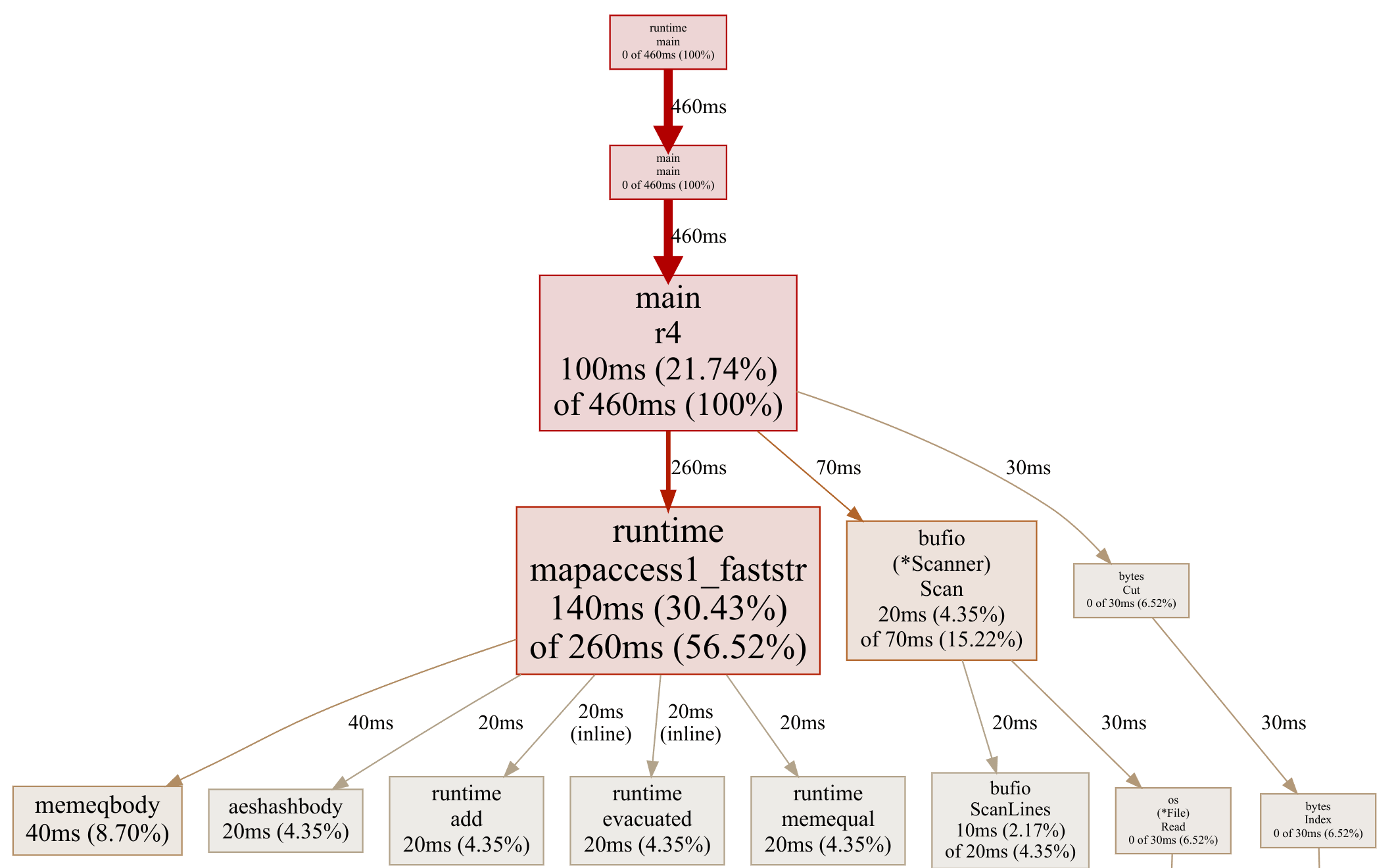

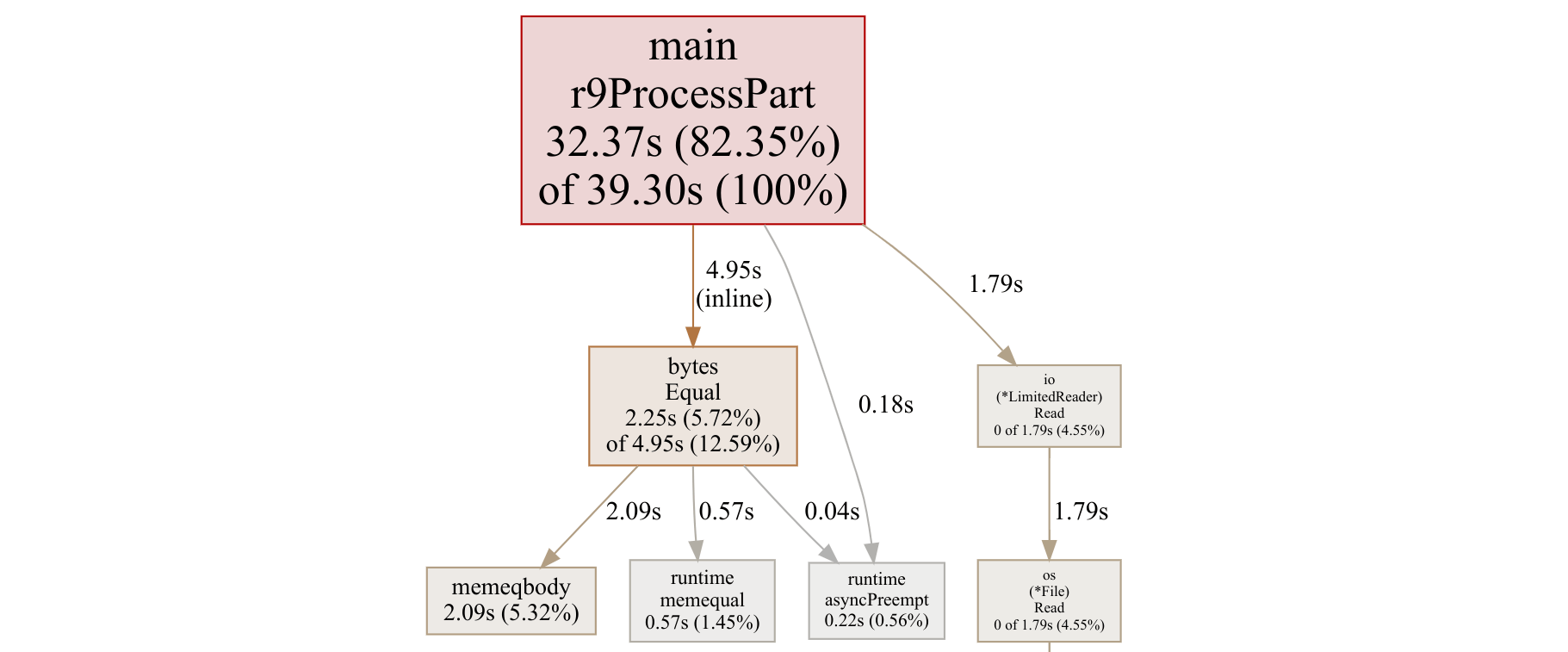

Interestingly, because all the real processing is now in one big function, r9ProcessPart, the profile graph is no longer particularly helpful. Here’s what it looks like now:

As you can see, 82% of the time is being spent in r9ProcessPart, with bytes.Equal taking 13%, and the file reading taking the remaining 5%.

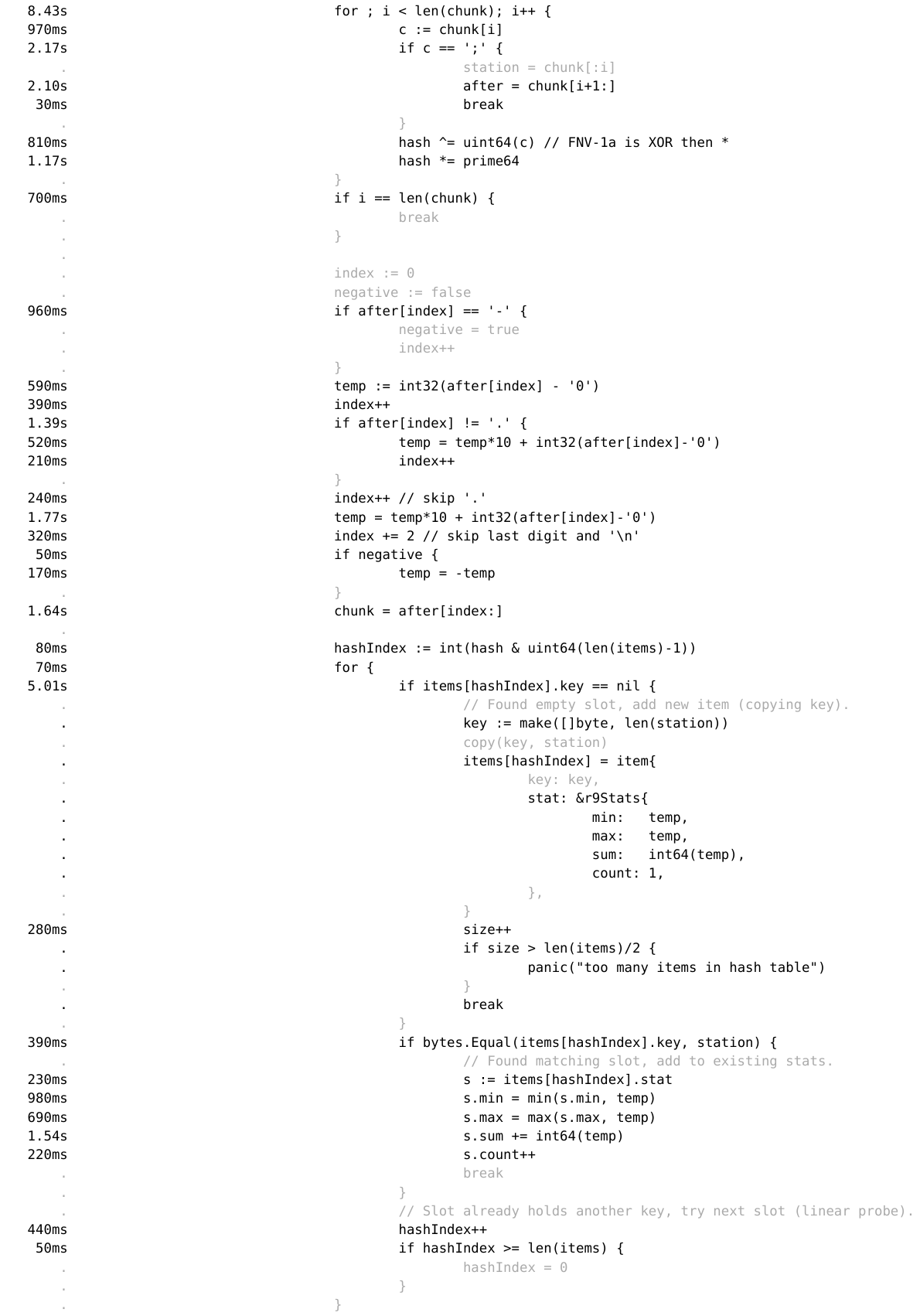

If we want to profile further, we have to dive deeper than the function level that the graph view gives us, and use the source view. Here’s the inner loop:

I find this report confusing. Why does if items[hashIndex].key == nil show as taking 5.01s, but the call to bytes.Equal shows as only 390ms. Surely a slice lookup is much cheaper than a function call? If you are a Go performance expert and can help me interpret it, I’m all ears!

In any case, I’m sure there are crazier optimisations I could do, but I decided I’d leave it there. Processing a billion rows in 4 seconds, or 250 million rows per second, was good enough for me.

Table of results

Below is a table of all my Go solutions in one place, in addition to the fastest Go and fastest Java solutions. Each result is the best-of-five time for running the solution against the same billion-row input.

| Version | Summary | Time | Times as fast as r1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| r1 | simple and idiomatic | 1m45 | 1.00 |

| r2 | map with pointer values | 1m31 | 1.15 |

| r3 | parse temperatures by hand | 55.8s | 1.87 |

| r4 | fixed point integers | 51.0s | 2.05 |

| r5 | avoid bytes.Cut |

46.0s | 2.27 |

| r6 | avoid bufio.Scanner |

41.3s | 2.53 |

| r7 | custom hash table | 25.8s | 4.05 |

| r8 | parallelise r1 | 24.3s | 4.31 |

| r9 | parallelise r7 | 3.99s | 26.2 |

| AY | fastest Go version | 2.90s | 36.2 |

| TW | fastest Java version | 0.953s | 110 |

I’m in the same ballpark as Alexander Yastrebov’s Go version. His solution looks similar to mine: break the file into chunks, use a custom hash table (he even uses FNV hashing), and parse temperatures as integers. However, he uses memory-mapped files, which I’d ruled out for portability reasons – I’m guessing that’s why his is a bit faster.

Thomas Wuerthinger (with credit to others) created the fastest overall solution to the original challenge in Java. His runs in under a second on my machine, 4x as fast as my Go version. In addition to parallel processing and memory-mapped files, it looks like he’s using unrolled loops, non-branching parsing code, and other low-level tricks.

It looks like Thomas is the founder of and a significant contributor to GraalVM, a faster Java Virtual Machine with ahead-of-time compilation. So he’s definitely an expert in his field. Nice work Thomas and co!

Does any of this matter?

For the majority of day-to-day programming tasks, simple and idiomatic code is usually the best place to start. If you’re calculating statistics over a billion temperatures, and you just need the answer once, 1 minute 45 seconds is probably fine.

But if you’re building a data processing pipeline, if you can make your code 4 times as fast, or even 26 times as fast, you’ll not only make users happier, you’ll save a lot on compute costs – if the system is being well loaded, your compute costs could be 1/4 or 1/26 of the original!

Or, if you’re building a runtime like GraalVM, or an interpreter like my GoAWK, this level of performance really does matter: if you speed up the interpreter, all your users’ programs run that much faster too.

Plus, it’s just fun writing code that gets the most out of your machine.

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!